It is a key thesis of Theosophy to the present time, that early Christianity stole “Christos” through syncretism, the very word its polemicists use to devalue the arguments of those that challenge its truth-claims. Early Christianity blended Jewish messianism with Greek and Mesopotamian elements to appeal to gentiles. The New Testament writers including Paul (the scapegoat of the dogmatists and a hated initiate), writing in Greek, used “Christos” over five-hundred times, utilizing the terminology of the mysteries indicating an initiate’s inner divine fire. Yet, as the church institutionalized (2nd-4th centuries CE), it degraded this esoteric and essentially universally-diffused principle of nature that leads to self-realization through trials, into a literal, historical personage as sole savior, enforced through the Nicene Creed. This simplification for the masses served power: exoteric worship of a carnalized Christ fostered dependency on clergy, enabling control over the masses through Roman decline. Gnostic alternatives, which preserved the mystical “Christos” as the inner principle were suppressed as heresies, consolidating the influence of the proto-orthodox Church. As Blavatsky noted, this subordinated universal wisdom, and prioritized faith over the declined institutions and method of initiation for societal dominance.

PRE-CHRISTIAN CLASSICAL ROOTS OF CHRISTOS IN ANOINTING RITUALS AND ROYALISM

Helena Blavatsky, in Theosophical Glossary (1892) and The Esoteric Character of the Gospels (1887) in this Short Lexicon of Titles and Terms used in Theosophical Literature, argued that Christians appropriated “Christos” from pre-existing pagan temple vocabulary, transforming it from an esoteric initiatory title into a literal, historical deity. “Chrestos” denoted a probationary disciple, or a candidate for hierophantship; and after initiation and anointing, they become “Christos” (the purified) after initiation. An example of this element in the mythos, is Jesus being initiated by John in the sanctified waters of Jordan as in the classical school of the Mandaeans or Sabians. When he had attained to this purification through initiation, long trials, and suffering, and had been ‘‘anointed’’ (i.e., “rubbed with oil,” as were Initiates and even idols of the gods, as the last touch of ritualistic observance), his name was changed into Christos, the “purified,” in esoteric or mystery language. Blavatsky cited Greek mythology like Apollo’s son Janus as “Chrestis” (initiate) and Asclepios as “Soter,” and equated this principle to the Buddha and Atman.

The earliest literary groundwork appears in Homer’s epics (c. 8th century BCE), where “chriso” refers to anointing as a ritual act of purification or preparation, often in heroic or divine contexts. In the Iliad, during the funeral games for Patroclus:

“They anointed [chrisan] themselves with olive oil” (Iliad 23.186)

Similarly, in the Odyssey, Odysseus is anointed post-bath:

“She anointed him with olive oil” (Odyssey 4.252).

These passages illustrate anointing as a mundane yet sacred act, prefiguring later mystical connotations without any messianic exclusivity.

In Theosophy, we take note that the Choephori (part of the Oresteia trilogy), Aeschylus uses “pythochresta” to denote oracles from the Pythian god Apollo:

“The oracles delivered by a Pythian god [pythochresta]” (Choephori 901)

Here, “chresta” implies prophetic utterances that are “useful” or “beneficial” divine revelations, linking the term to oracular intermediation. This predates Christianity by over 500 years and shows “Chrestos” as a descriptor for divine messages, not a personified deity.

In his Histories, Herodotus employs forms of “chreō” and “chrestos” for oracular declarations. For instance, describing Persian consultations:

“The oracle declared [chreō]” (Histories 7.11.7; see also 7.215, 5.108)

These refer to prophetic responses from gods, positioning “Chrestos” as a soothsayer or explainer of divine will, akin to a ritual intermediary. Likewise, in Philoctetes, the term “chrestes” appears in prophetic context (Sophocles, Philoctetes 1333), tying into oracular mysticism, where anointed figures interpret divine signs.

In the narrative of Ion, Euripides uses “chrestes” for oracular servants or seats:

“The oracular seat [chrestes]” (Ion 1321)

This evokes temple initiates or prophets anointed for divine service, reflecting mystery cult practices where “Chrestos” denoted a probationary disciple who becomes “Christos” (purified) after initiation.

These examples from 8th-5th century BCE texts demonstrate the “Christos/Chrestos” terminology as central to Greek oracular traditions, often connected to Apollo (the “Soter” or savior god) and mystery cults like those at Delphi or Eleusis. Initiates, called “Chrestoi,” underwent purification rituals symbolizing death and rebirth, mirroring esoteric paths to divine union, which are concepts later found in Christian baptism and resurrection, although stripped of their initiatory depth.

Mesopotamian influences on “Christos” are more foundational, feeding into Greek practices from cultural exchanges during the Bronze Age and post-Alexander Hellenistic periods. In Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian traditions concepts of anointing (with oils or divine essence) signified royal or priestly consecration, while prophecy involved ecstatic intermediaries receiving divine messages. These “anointed” figures were seen as bridges between gods and humans, predicting fates through omens, dreams, or ecstatic speech, paralleling Greek oracles and prefiguring the Christian concept of the “anointed one.” Unlike Christianity’s singular focus, Mesopotamian “anointing” from Old Babylonian Omen Texts (c. 2000-1600 BCE), the Akkadian Oracles concerning Esarhaddon of the neo-Assyrian period, the ecstatic prophets of Mari Prophetic Texts (c. 18th century BCE) and Divination in Hittite and Mesopotamian Texts (adapted from earlier Sumerian, c. 2000 BCE), were all pluralistic, applying to kings, priests, and prophets in ritual contexts. Mesopotamian rituals, like those in the Enuma Elish creation epic involved anointing gods (kings) for cosmic order, with prophets as their divine mouthpieces. These ideas diffused westward through trade and conquest, even shaping Greek oracular tradition (e.g., Apollo’s parallels to Mesopotamian Ninurta).

Early Christianity emerged in a Hellenistic world saturated with these ideas. This evidence directly refutes Christian assertions of doctrinal uniqueness, as CHRISTOS was neither original nor exclusive to Jesus. Repeating our earlier point, in pre-Christian eras, CHRISTOS denoted anointed prophets or oracular servants across cultures, common in Greek initiatory mysteries and Mesopotamian prophecy through intermediaries. The Septuagint (3rd-2nd century BCE) translated Hebrew “Mashiach” (anointed) as “Christos,” bridging Jewish kings and priests with Greek terms, but this was syncretistic, not innovative. Early Christians, emerging in a Hellenistic cultural milieu, claimed Jesus as the singular “Christos” (see Acts 2:36), ignoring its pagan ubiquity. This appropriation masked borrowings: resurrection motifs from Greek mysteries (e.g., Dionysian and Eleusinian) and Mesopotamian dying-rising gods, reframed as unique salvation.

Blavatsky condemned Christianity’s “redaction and appropriation,” degrading an esoteric path of uniting personality with the immortal Ego into literal deity worship as in its exoteric dogmatic form. The deep philosophy of the mythology holds the key to understanding Jesus not as a unique historical Christ, but as an adept embodying great principles to humanity, therefore, she rejects the “carnalized” Christian version as a myth. This reflects scholarly views on syncretism in early Christianity, involving influence from Hellenistic Judaism, Stoicism, mystery traditions, and Near Eastern religions.

In ancient Greek contexts, CHRISTOS did derive from the verb “chriō” (χρίω, “to anoint” or “rub with oil”), often connoting ritual purification, prophetic revelation, or service to an oracle. Frequently interchangeable with “Chrestos” (Χρηστός, meaning “useful,” “good,” or “prophetic” due to ancient vowel shifts and semantic overlaps), this usage was embedded in oracular mysticism, particularly at sites like Delphi, where intermediaries (e.g., the Pythia) delivered divine messages. The term applied to prophets, soothsayers, or initiates in mystery cults, symbolizing a state of divine enlightenment or anointing after trials, far from the Christian monopoly on it as a title for a unique messianic savior to usurp those very traditions.

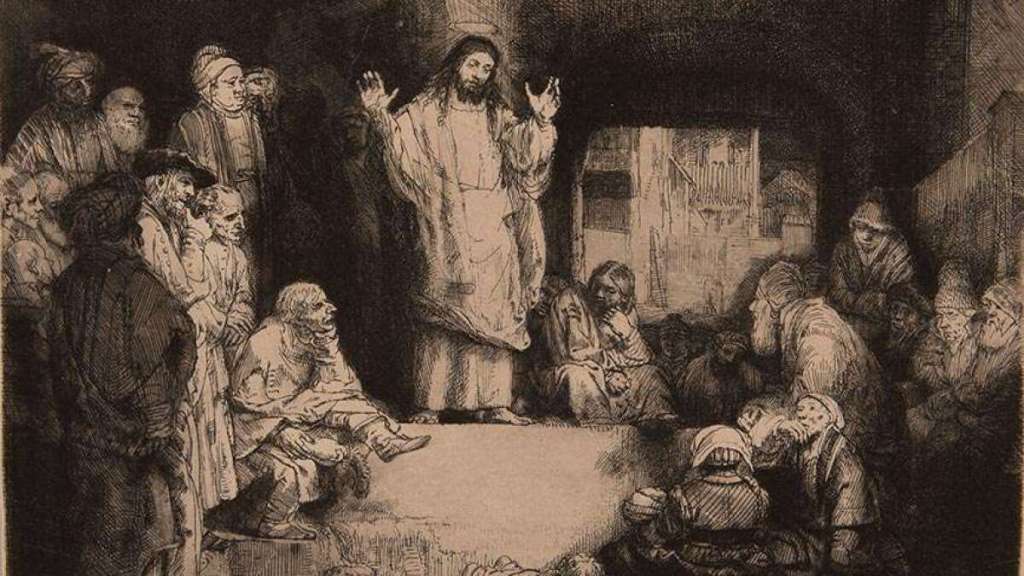

JESUS THE MARTYRED ADEPT AND THE HISTORY OF ADEPTS

Our position should be to question and respect Jesus as nothing more than a man, master (rabbi or teacher to his disciples), initiate and martyred adept. In Theosophy, the men behind the Theosophical Movement considered Jesus as a martyred adept (one of the greatest among them) within the context of a long history of adepts; not centered on any particular special adept, or character as is done in any given religion. These men had said, that in a place of theirs were kept statues of various adepts, and a statue of Jesus was among them. None of these individuals, no theosophist in fact, would in their right mind objectively argue, or think of Jesus as greater than Confucius, Sextus, Pythagoras, Philo of Alexandria, Siddhartha, Nagarjuna or Shankaracharya (see The Spanish Alumbrados: Origin of the Term ‘Illuminati’) to name a small few in the record of human history. Theosophical Teaching does not combine them all into a hierarchy or arrange them in a special angelology, though some have tried; and are capable of being skeptical of their historical existences or teachings. Each special character always positions themselves authoritatively (or those that do) in a certain manner, and all cannot be certainly true on their face.

The habit of exclusion, inclusion or arrangement of hierarchies is an innovative quality of a religion (with its particular accepted prophets), an encompassing one (like Islam with its many numbers of prophets it considers), or a syncretic religion (e.g., Manicheanism), whereas I rather maintain the “History of Adepts” in a realm of humanist, social, ethical and philosophical teaching.

REFUTING WORSHIP AND INTERMEDIARIES: THEOSOPHY ON DIVINE POTENTIALITY

There should be no worship of Jesus or any gods in any collective space of esotericists or practitioners. We admire the gods (The Garden Philosopher: Epicurus of Samos on the existence of the Gods). We do not worship the gods. Man has in their constitution, their being, a divine potentiality, and this divine potentiality is in every atom, of which we are composed of. Man has no need for worship of anything, but admiration for the reflection of that supernal quality in all life. Through man’s own nature, human beings can achieve degrees of proximity and harmony — the great sword against our own darkness. The argument of a Theosophist is most likely and consistently to be closer to the Jew and the Muslim mystic when it comes to where our perception should be focused, in rejecting the requirement of any concept of an intermediary, and Christos is not understood as an intermediary, or medium. The fear, that the decline of Christianity will lead human-beings to idolatry and polytheism is not entirely true, especially since polytheism does not fully characterize the entirety of the ancient world’s beliefs. Theosophical Teaching proposes adherence to pre-Christian Oracular applications of “Christos,” and refutes the doctrinal uniqueness of Christianity as we have come to know Christian teaching, particularly when it comes to the language of Christianity, which is focused on refuting every other religion and placing itself as the only Truth. This represents a degeneration of Wisdom. Jesus as perfected exemplar and his teachings and example being a guide to living a holy life in communion with God and the world beyond constitutes a theology already existent in the ancient mysteries, overlayed with new mythical elements. The mythical elements are not required for any spiritual discipline.

This position on human immanent divine potentiality is not a modern teaching. This is the secret teaching. It is at the basis of science and philosophy itself among the Pre-Socratic thinkers. To know it is a completely different matter, and this challenges both theological and physicalist notions about the nature and evolution of the elemental substance of sentient awareness evolved to be capable of pondering its own origin from the celestial stars and beyond. This entire way of understanding the function of religion comes into some conflict with Christianity, because of particular features in Christology, which often historically defined itself in opposition to the scientific-philosophical approach of “the pagans.” In the twentieth-century, Theosophists get distracted into unfortunate new theological innovations of their own (e.g., Bailey, Purucker, Steiner, Besant and Leadbeater), which have become caricatured through New Age ideas, and serves as strawman from which Christians have critiqued Theosophy. However, certain earlier positions do have a strong basis in scholarship and early European philosophy.

HOW DO I DEPICT JESUS

Whoever wrote the Gospels were definitely inventing dialogue for Jesus, and its Hellenized writers were constructing a Hellenic-Jewish narrative and setting for their literary character, blending it with a possibly historically martyred individual of that name. Therefore, when I speak of Jesus, I refer to Jesus as the “literary Jesus,” “semi-mythical Jesus,” or “literary figure (or depiction) of Jesus.”

When I am speaking from a perspective of theatrical immersion within the texts to affirm some of its mystical elements, then I do not refer to the Jesus within the text as such and maintain the underlying esoteric truth in speech. I would, however, never invoke or speak in a manner that advises Jesus-worship, but rather point to his ways, mannerisms, semi-ascetic contemplative living and radicalism as guidance — as philosophy as “way of life” against materialism. The use of Jesus however to impose authority, tradition, power or domination on others through cult-personalities, associations, institutions, governments and so forth is not the Christian way to me. I very much think a non-Christian is capable of understanding the precepts of Jesus, and even with my perspective, it is understood in as similar of a way to a priest. I can give sermons myself to Christians, and I think they would very well understand in a deeper way from their perspective. Depending on the person and their needs, I invoke the human character, the mystical element, or the democratized element of God’s reflection in all life. If the individual uses Jesus like a talisman to stay “on the path,” this does not really interfere with the instruction about maintaining the strength within on “the Path to Wisdom” capable of being given.

THE NEW EMPIRE’S MANTLE: CHRISTOS IN PRE-CHRISTIAN CONTEXT

“Christos” is not a novel Christian innovation, but a term borrowed from Hellenistic, Greek oracular and Mesopotamian divinatory traditions predating Christianity by centuries. The pre-Christian applications of the “Christos” (Χριστός) concept, signified anointing, purification, prophecy, and divine intermediation in rituals and mysteries. Christianity’s historization of Christos is a simplification ecclesiastical power, appealing to the poor and uneducated, as noted by Roman observers.

The Church’s imperial role and authority set itself up as an obstructive force to the adepts’ struggle against worldly power, which adepts combat; and which Christianity have obtained and maintained at all costs. Adepts are those who have brought out of themselves their diviner portion (the real adept of every mortal) and live in accordance with its nature in relation to their being; and who grow exponentially in wisdom (often possessing super-sensible qualities) from this secret knowledge of our true nature. The struggle among most (not all) adepts in this history is against powerful established institutions, and who have often become victims.Many have accepted a position of subordination to the established Christian perspective and adjust their theories about Jesus accordingly. This is not the approach of Theosophy, because the history Theosophy focuses emerges within a global context of the history of adepts, and even trans-national ties among adepts. Christianity’s two-millennia dominance has narrowed Western history to clerical power and theological questions about the nature of Jesus Christ, then trying to get away from the marriage of Christian institutional power, finance and the State.

True theosophy is not limited to being a projection of one particular individual’s conditioning, or psychology, but the scope of any particular individual or community in understanding what is being said here is a great determinant in the success of the underlying ideal of the movement of Esoteric Wisdom throughout the Ages, as they say. Christians could help in this affair, but Christianity has been a long two-thousand-year obstruction of the work and tradition of other sages at the basis of so-called Western Civilization. This has suppressed the work and tradition of other sages at the basis of so-called Western Civilization actual lineage of sages against prophetic impositions from David, Jesus, or Muhammad. and the Scientific Age thrown over its legacy as a story of triumph against the ancient Pagan world of superstitious ignorance. The history reveals the ties between humanity and is therefore not merely an abstract notion of unity. There is more to this world than Aristotle and St. Aquinas, and yet our world since Christianity emerged in its dominant position has been structured by a limited depiction of Western Civilization’s timeline of the origins and purpose of science, philosophy and its political traditions.

MYSTERY NEW TESTAMENT WRITERS’ SYNCRETIC INNOVATION OF HELLENIC AND JEWISH MYSTERIES

Now, there is undeniably a syncretic habit to very early Christianity that demonstrates how the term Christos and its associated ideas were appropriated, historicized, and simplified into an exoteric dogma to consolidate ecclesiastical power and appeal to the masses, particularly the poor and uneducated. Such was the keen observation of Roman intellectuals when the nascent religion was attempting to increase its numbers. Increasing numbers is all the Christians cared about, in their belief that the Gospel would save the world. This is the crassness of it. This partially explains the offensive simplicity of Christological dogma about the nature and purpose of Jesus and his relationship to humanity. The Christian dogma becomes a crude carnalized appropriation of a true mystical and metaphysical doctrine in Mesopotamian and Greek oracular traditions of anointing, exploited through the character of the singular figure Jesus in the New Testament mythos.

There exist many works in many cultures and traditions (e.g., in classical Greek and Indian philosophy) extolling the path (or practice) of the devotional approach to self-realization (or goal of union with the Divine), in which the practitioner comes into (or claims to come into) dialogue with a [sense of a] being (or aspect of their being) greater than (or immanent within) themselves, in which elevation of mind and an extension of love emerges (or envelops them) and seems from our finite perception — boundless, indescribable and ineffable. Human language tries to define these experiences, and there is complication in the sense of “direction,” which indicates from (a) the view of psychology: neurological phenomena; (b) the view of physics: dimension in relation to the nature of matter and neurological phenomena itself; (c) the view of mystics: interaction with subtler quality of nature (or matter). The Christian religion seems entirely based upon this devotional approach, which is however dogmatically imposed upon the character of their nabi (prophet), guide or master in Jesus (e.g., like Krishna in the Bhagavad-Gita) who takes the role of a celestial monarch (a political innovation of Mesopotamian origin) in a trinitarian concept of God’s Unity.

Within this trinitarian concept are the limitations through which Christians attempt to explain the relationship between the Divine and the Worlds of Matter, in which humanity lives, loves, struggle, dies and transitions after physical life. However, outside of the romanticized ideal, in reality from this comes the exoteric perspectives of the conventionalists who portray Jesus as a superior being who never farted and took a dump before giving a sermon; and who the whole world should be at his feet worshipping and kissing for all eternity. This style of Religion has contributed to the decline of Religion, but also cyclically contributes to a rise of Religious Worship during times of economic desperation, war and disaster.

Leave a comment