Imagine stepping into a river, only to find that both you and the water have transformed in the blink of an eye. “No man ever steps in the same river twice,” declared Heraclitus. This simple yet profound observation captures the fundamentals of his philosophy; and one that revolutionized how we understand change, unity, and the cosmos. In an era dominated by myths and gods, Heraclitus elevated fire as the primal element generating eternal transformation. His ideas not only laid the groundwork for Western philosophy, but continued to ignite modern thought, from physics to social revolutions.

PRE-SOCRATIC PIONEERS AND THE PATH TO RATIONAL INQUIRY

The term “Pre-Socratics” refers to a diverse group of ancient Greek philosophers active primarily in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. These thinkers, including Thales of Miletus, Anaximander, Anaximenes, and Parmenides, broke from traditional mythic explanations of the universe — tales of gods like Zeus hurling thunderbolts or Poseidon stirring the seas. Instead, they pursued natural, rational accounts of existence, cosmology, and human life. Labeled “Pre-Socratics” to differentiate them from Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE) and his followers like Plato, who pivoted toward ethics, politics, and the human soul, these early philosophers pioneered systematic inquiry into physics, metaphysics, and the origins of all things.

This shift marked the dawn of Western philosophy and science, replacing supernatural narratives with observable principles and logical deduction. For instance, Thales posited water as the fundamental substance (archē) of the universe, while Anaximander envisioned an infinite, boundless essence (apeiron). Their work transitioned thought from poetic or religious frameworks to a structured, intelligible worldview, deeply influencing Plato and Aristotle. Understanding this context is essential, as it demonstrates how Pre-Socratics like Heraclitus bridged the gap between myth and modernity, encouraging further inquiry into the apparent stability of reality.

Heraclitus belonged to the Ionian tradition, which flourished in the Greek city-states of western Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), such as Miletus, Ephesus, and Phocaea. These colonies, settled by Greeks from the mainland around 1000 BCE, became crucibles of innovation due to their exposure to diverse cultures, including Persian, Egyptian, and Babylonian influences. Ionians sought a single primal substance or principle (archē) to explain the cosmos, favoring rational explanations over mythological ones.

Early Milesians like Thales (who chose water), Anaximander (the boundless apeiron), and Anaximenes (air) emphasized material principles that were either stable or capable of transformation through processes like rarefaction and condensation. However, none elevated fire to the primary role. This tradition’s emphasis on unity amid diversity set the stage for Heraclitus, who radicalized it by introducing dynamism and conflict as core to existence.

HERACLITUS, THE OBSCURE AND HIS ROOTS IN THE IONIAN TRADITION OF ASIA MINOR

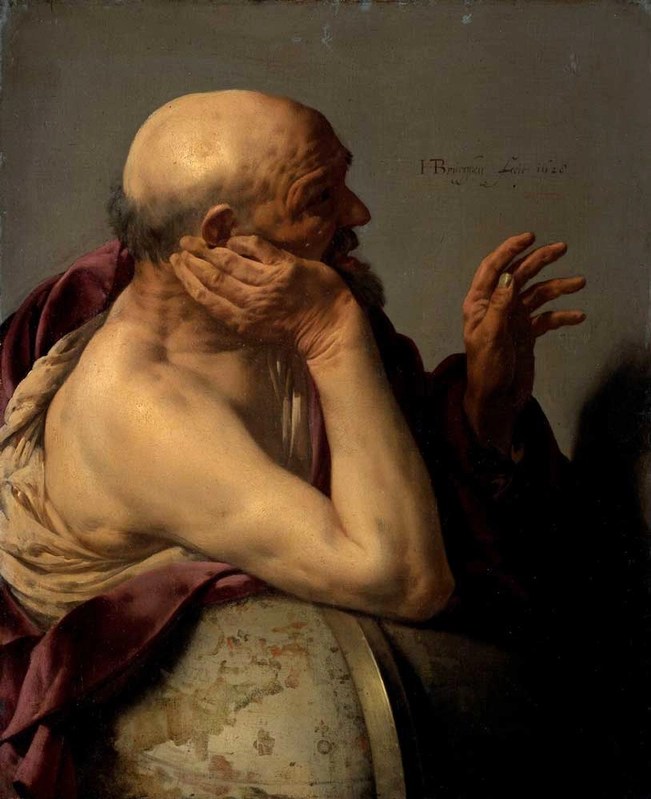

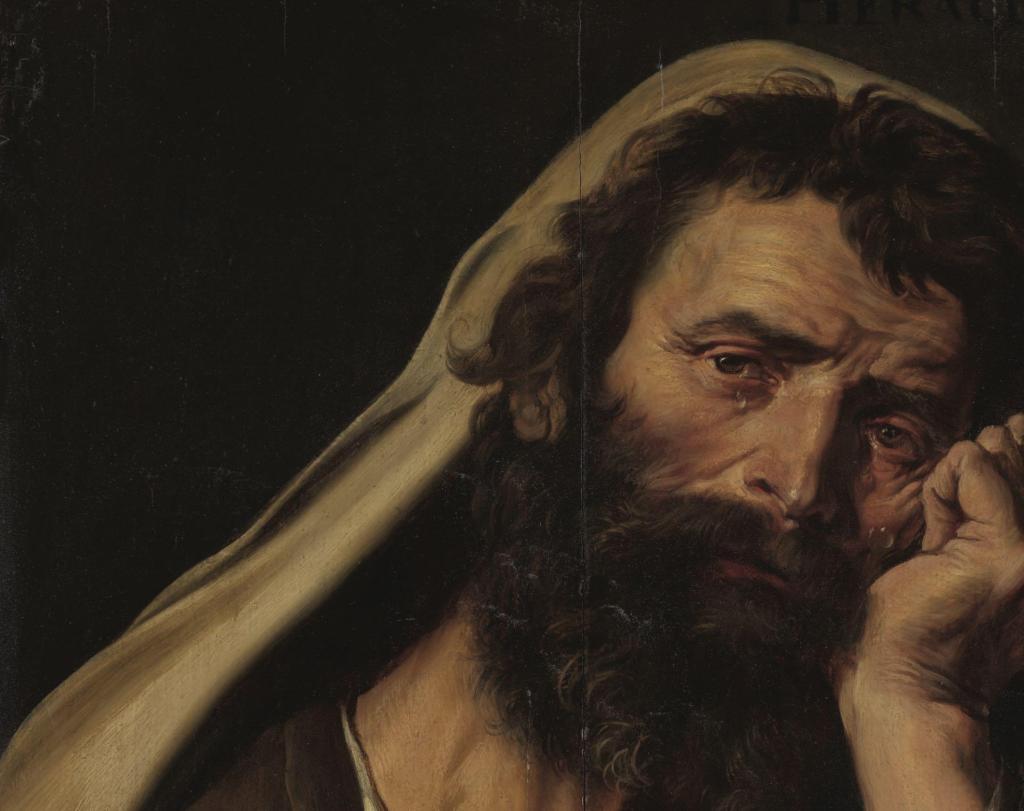

Born around 535 BCE in Ephesus, a bustling Ionian port city renowned for its Temple of Artemis, Heraclitus, son of Bloson lived until about 475 BCE. Little is really known of his personal life. Ancient sources portray him as aristocratic, melancholic, and disdainful of the masses, earning nicknames like “The Obscure” or “The Weeping Philosopher.” He reportedly deposited his sole work, a book of aphoristic fragments titled On Nature, in the Temple of Artemis, where it survived — quoted by later authors like Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics.

Historians connect Heraclitus to the Ionian tradition mainly through geography: Ephesus’s proximity to Miletus aligned him with the Milesians’ quest for a unifying principle. Thematically, he built on their ideas but critiqued their static monism, arguing that reality is not a fixed substance but a process of perpetual change. Unlike his predecessors, Heraclitus used fire not just as a material but as a symbol of flux, governed by an overarching LOGOS or rational order that structures the universe’s transformations. This made him the founder and chief proponent of PRIMAL FIRE within the Ionian framework, blending cosmology with profound insights into human perception and ethics.

HERACLITEAN PHILOSOPHY ON PRIMAL FIRE

At the core of Heraclitus’s thought is primal fire (pyr aeizōon, or “ever-living fire”), which he elevated as the fundamental substance and process of the cosmos. This marked a pivotal shift from the static materiality of earlier Ionians to a dynamic, living principle. Fire, for Heraclitus, is not merely a literal flame but a metaphor for constant transformation: it consumes, renews, and balances in measured cycles. As he famously stated:

“This world, which is the same for all, no one of gods or men has made; but it was ever, is now, and ever shall be an ever-living fire, with measures of it kindling, and measures going out.”

This ever-living fire symbolizes flux (panta rhei, “everything flows”), the idea that reality is in perpetual motion. His iconic river analogy in Fragment 91: “You cannot step twice into the same river; for fresh waters are ever flowing in upon you” illustrates how change is the only constant, challenging our illusions of permanence. Yet, amid this flux, Heraclitus posited a hidden unity: the unity of opposites. In the unity of opposites and strife (or change), the cosmos is an ordered process governed by LOGOS, where conflict drives harmony. Opposites coexist and depend on each other, with conflict (polemos, or strife) driving harmony. Fire embodies this tension. It destroys (death of one form) while creating (birth of another).

Fire as the arche and symbol of flux is an ever-living, transformative principle from which all things arise and to which they return. It teaches, that this world ever was and is and shall be: an ever-living fire, kindling in measures and being extinguished in measures. Fire is not merely literal physical flame, but represents constant change.

Hence, in his fragments (e.g., 36 of John Burnet’s numbering, 1920), Heraclitus states that HO THEOS is day and night, winter and summer, war and peace, surfeit and hunger.

Governing this is the logos, an intelligent, divine principle immanent in the world — not an anthropomorphic god, but a rational measure ensuring balance. All things are “an exchange for fire, and fire for all things, just like goods for gold and gold for goods” Heraclitus taught. Transformations follow measures (balance), preventing chaos; while strife is justice, maintaining equilibrium.

True wisdom, Heraclitus argued, involves awakening to this hidden structure amid apparent disorder, aligning the human soul (also fiery and rational) with the cosmic logos.

Elevating fire as the fundamental substance and process of reality marked a shift toward dynamic change over static materiality with natural mystical implications. Modern philosophy and literature have adopted the positions of those that were critical of the Heraclitean overall style of riddles, complexity, double-meaning and abstractness. Called “obscure” by critics like Aristotle, this deliberate complexity forces readers to engage actively, to make room for and induce change. Those minds he influenced bore philosophies that aspired to more than philosophical contemplation, but action. This style explains the author’s style and overall purpose. Not everything ought to be written clear and precise for comfort, as the obscured is not itself easily cognizable. Writing that is imaginative, scaled, abstract and inductive still serves its purpose.

SUMMATION, LEGACY AND ADOPTIONS OF HERACLITUS’ PHILOSOPHY

Heraclitus built on earlier Ionian Tradition, but critiqued Milesian monism for its rigidity, rejecting static substances for a dynamic one, favoring fire’s vitality to explain observed change better than water, air, or apeiron. This eternal living-fire aligns with the divine (an immanent, intelligent process, not anthropomorphic gods) and the human soul, and true knowledge awakens to its obscured unity amid apparent flux. While some pair him with the Pythagorean Hippasus of Metapontum who also posited fire as origin source (or archē), Hippasus hailed from the Italian (not Ionian) tradition and lacked Heraclitus’s integration of flux and logos into a holistic cosmology.

His ideas rippled through history: Plato contrasted Heraclitus’s “becoming” with Parmenides’s “being,” while Stoics adopted his logos and cosmic fire in their pantheistic worldview. In modern times, process philosophers like Alfred North Whitehead echoed his emphasis on change, and even quantum physics resonates with his flux. Remarkably, we can trace Heraclitus’s influence on 19th-century Black abolitionists like David Walker. In his 1829 Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, Walker transformed the “primordial fire” and logos of archaic traditions into a “spark of the Eternal,” — a divine, rational force igniting resistance against slavery and static submission or passiveness. His declarations like “The spark of liberty is in every man’s bosom, white or black” and calls to “rise up like men” moves Heraclitean fire into revolutionary action, blending it with Stoic, Christian, and African traditions to challenge oppression. This demonstrates how Heraclitus’s primal fire transcends antiquity, fueling movements for justice and transformation.

PANTA RHEI (πάντα ῥεῖ. “Everything flows.”)

Leave a comment