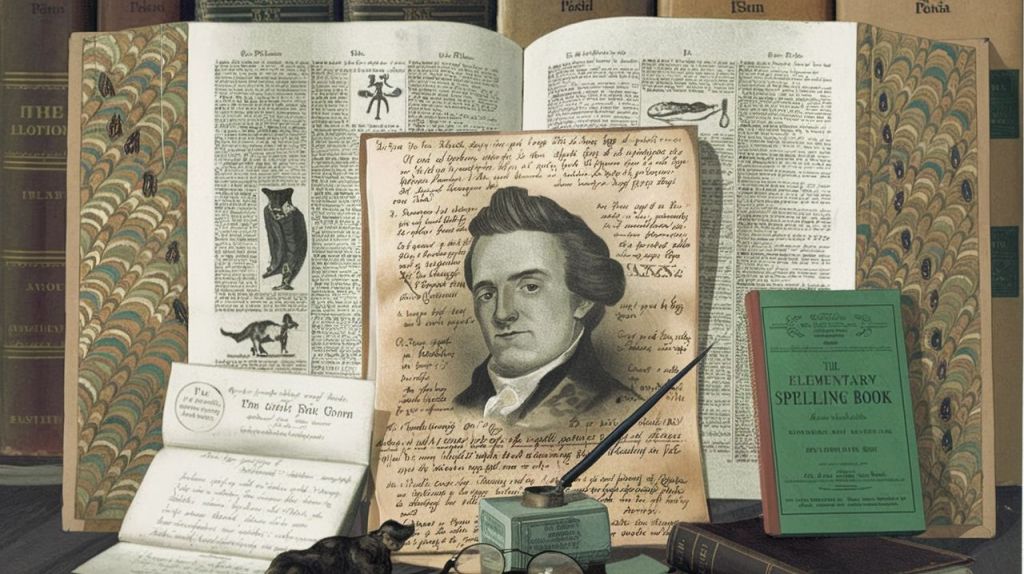

Noah Webster, Adams and other early Americans emphasis on divergence from Britain demonstrates how Federalists sought to create early American identity through changes to institutions, language, and colonial education to legitimize the new republic. Mayflower descendant Noah Webster (1758-1843) is considered the father of American education and the American dictionary. Webster is accompanied by many other famous Americans whose ancestry traces back to the 102 original Pilgrims who landed in Plymouth (1620), including at least eight presidents. Another Mayflower descendant who we recognize is American writer and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. Noah Webster founded the Federalist newspaper “The American Minerva: Patronage of Peace, Commerce and the Liberal Arts,” representing an expression of the Pilgrims’ early American nationalism.

This understanding of his place within colonial history enlightened him with a sense of destiny. In the simplest explanation, the man valued learning and grew up with a love of history. This resulted from his surroundings and reflections coming from an important New England family. Noah Webster’s father, Noah Webster Sr. was a descendant of John Webster, an early governor of Plymouth Colony (see Noah Webster: The Father of American Education).

“The American Minerva” was New York’s first daily newspaper. Webster was a fierce defender of the administrations of George Washington and John Adams, and he espoused a high scriptural theology.

In the early national life of America, Webster was a schoolbook author, itinerant lecturer, newspaper editor, Federalist pamphleteer, epidemiologist, and copyright advocate (Tim Cassedy, 231). Webster echoes John Adams in 1785, reflecting a time in early colonial American culture when European Americans began to firmly establish a separateness, or cultural independence from Britain.

Noah Webster (father of the American dictionary) began his address thus:

“It is the singular felicity of the Americans, and a circumstance that distinguishes this Country from all others, that the means of information are accessible to all descriptions of people.”

An excerpt from his penned address to “The American Minerva”:

“But Newspapers may be rendered useful in other respects. In America, agriculture and the arts are yet in their infancy. Other nations have gone before us in a great variety of improvements. They have, by observations and experiments, discovered many useful truths of which the people of this country are yet ignorant; or which are not generally known and applied to practice. The compiler of a paper, who will take the trouble to select from authors, those facts and principles in the arts which are found in other countries to abridge labor and render industry more productive, will perform a most essential service to his country. A useful fact, a truth, which cost some ingenious enquirer the labor ten year’s experiment, may be contained in a single column of a Gazette, and diffused among millions of people. Some exertions to collect such useful truths for this paper will be made by the Editor, and he hopes, with success.”

I did not get my idea from Noah Webster, but as I was creating the name for my site at first, the title was taken, so I added the n to Minerva. I had discovered THE AMERICAN MINERVA newspaper, which changed its name, and later became The Globe, then merged with The New York Sun. I began to notice, that in searches, this site is sometimes incorrectly referred to as The American Minerva (not Minervan). It is impossible to have Minerva in your name and not be devoted to the same principles and interest. The representation of America as Columbia, which is an iteration of the Roman and Etruscan goddess Minerva goes back to the culture of the early American Republic.

The symbol of America as the Goddess of Wisdom, Commerce and the Arts in Columbia (first represented in a poem by a freed Black woman) was replaced by the Lady of Liberty, although Minerva is a Savior-Goddess, or Goddess of Liberation, which still encapsulates the meaning of REPUBLICANISM. As America, wisdom-intelligence bears the shield of the institutions of the Republic against tyranny (the loose tiger) and political poisons that lead to corruption and eventual decline of the Republic. In early American paintings, Columbia is depicted standing beside Native Americans (some show subjugated Black slaves however) or entirely changed into a Native American or a Black Woman as America alongside a female representation of Europe.

For Noah Webster, he speaks of theo-sophia, or the Wisdom which is from above using Psalms 90:12 and Job 28:12 in his definition of WISDOM. In Scriptural theology, Webster states in his definition, wisdom is true religion, godliness, piety, knowledge and fear of God, and obedience to his commands. Webster’s philosophy relates to Blavatsky, when she stated in a manuscript (London, 1890) answering Russian philosopher Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov, that ‘Theosophists worship the wisdom that is from Above.’

“But where has he found Neo-Buddhism in our teachings? There is none, but simply a considerable amount of old Christian Gnōsis. Besides, the whole of our literature proves that real Theosophists, worshipping universal wisdom, worship in reality the same wisdom which has been proclaimed by St. James in the third chapter of his Epistle, i.e.,

. . . the wisdom that is from above (σοφια ανωθεν [which] is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, and easy to be entreated, full of mercy and good fruits, with out partiality, and without hypocrisy, avoiding, on the advice of the same Apostle,

wisdom that is earthly, sensual, devilish (ψυχικη, δαιμονιώδης).

Therefore, if trying to follow to the extent of our strength the higher wisdom, we use the word Bodhi, instead of Sophia, it is first because both words, the Sanskrit and the Greek, are synonymous, and second because for every European Fellow we have some fifty Asiatic Fellows — Brāhmanas and Buddhists.”

This explains the difference, given Webster’s limitation in his love for learning and religious Wisdom, much like the Christian Kabbalists — for whom The Bible is center. Also, The American Minervan is not a newspaper or a journal about Art and Architecture, though I am able to incorporate such history. The focus is more on Martial Spiritual Discipline, Religion (to a fuller extent) and Philosophy from an eclectic and theosophical/illuminationist approach.

Many of these early thinkers like Noah Webster thought less like the modern American evangelical and more similarly to Giovanni Pico, “that all philosophies and all religions have attained a portion of the truth, Gianfrancesco said, in effect, that all religions and all philosophies – save the Christian religion alone – are mere collections of confused and internally inconsistent falsehoods.” (Schmitt, Gianfrancesco Pico Della Mirandola and His Critique of Aristotle).

Webster and Adams, like Pico (a student of his uncle Girolamo Savonarola) subordinates the realm of philosophy and knowledge to “the self-subsistent reality of Christianity.”

This however does not define all the founding fathers and framers of the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, just like the fact there were several anti-racist White people in the early history who fought against slavery.

“America’s religious and civil liberty were uniquely drawn from Christianity,” according to Noah Webster (Dr. Paul Jehle, Noah Webster’s 1828 Dictionary), and he believed all children, under a free government should be taught the Liberal Arts and the principles of Christianity. He acted on these beliefs by being active in his communities, founding an Academy in 1816, directed the Hampshire Bible Society, becoming alderman, a member of the General Assembly, a councilman and a judge.

Noah Webster wanted the youth and people of the early Republic to understand and preserve the values behind his educational textbooks, and some Americans did not like him. He also often made a distinction between a republic and a democracy. There is a philosophy of universal unity and national integrity that imbues his work in a nation he hopes embraces both principles of change and changelessness. The abridgement and restraints of law are essential to civil liberty, Webster taught.

The argument, that American political thought shifted from classical republicanism toward a more democratic, popular-sovereignty-based model during the ratification debates, creating a distinct American identity at the expense of deeper republican traditions is important to historian Gordon Wood’s analysis.

In A Critical Look at Hayward’s Review of the Liberal Republicanism of Gordon Wood, it is explained that:

“American political theory and thinking might have republican roots, but this unfortunately changed after the Federalists’ appeal to the sovereignty of the People to ratify the Constitution.”

Gordon S. Wood attributed this change to the Federalists. The emphasis shared by many thinkers at the time such as Webster on developing an independent nation and national language (divergent from the standards of Britain) led to the creation of a distinct American political theory, “but only at the cost of eventually impoverishing later American political thought” (The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, 2004).

In Hayward’s critical review, it is explained how Wood in his work, “The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787” (1969), argues that pre-Constitutional American thought was deeply rooted in classical republicanism, a Whig-inspired ideology emphasizing virtue, civic duty, mixed government, and the common good over individual interests. This drew from ancient models (e.g., Rome, Machiavelli) and 18th-century thinkers like Montesquieu (see The Loose Tradition of Republican Writers). However, to secure ratification of the U.S. Constitution (1787–1788), Federalists like James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and others pragmatically shifted rhetoric toward popular sovereignty, and the idea that ultimate power resides in “the People” as a unified, sovereign body. Although this change was not immediate post-ratification, it became apparent after the debates. This appeal democratized the discourse, transforming REPUBLICANISM into something more egalitarian and individualistic, which Wood sees as a pivotal (and somewhat lamentable) break from classical ideals. Wood’s critique views the shift as innovative but ultimately diluted republican roots.

Part Three, Chapter IX called “The Sovereignty of the People” in “The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787” details how this tactic “secured the triumph of democratic ideas” but eroded the hierarchical, virtue-centered republican framework. This framework is in keeping with the ideals of Noah Webster and underlies his sense of destiny to meet the need to educate Americans, and precisely the children.

Where Webster comes up is when Wood explicitly blames this rhetorical pivot on the Federalists in Creation. Wood portrays the Federalists as strategic innovators who co-opted anti-Federalist democratic language to win ratification. A tendency many of us know well with the history of occultists, Webster in this early history of American journalism authored pro-ratification essays (e.g., under the pseudonym “A Citizen of America”). These essays of Webster emphasized national unity and popular consent, aligning with the sovereignty appeal.

Noah Webster is cited in Creation as a key example and is further discussed alongside figures like Hamilton and Madison as part of the broader Federalist effort to forge a consolidated national identity.

Wood’s Creation frames the Federalist era as the “creation” of a uniquely American political theory breaking from British monarchical and aristocratic norms toward a republican (later democratic) nationalism.

Thinkers like Webster embodied this by promoting cultural independence: his 1783 Dissertations on the English Language advocated spelling reforms (e.g., “color” over “colour”) to foster a distinct American English as a “bond of national union.” While Wood references Webster’s nationalist writings in Creation (e.g., on education and unity), language reforms are more prominent in Webster’s own works and Wood’s later books like The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1991).

In Wood’s The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (2004), he reflects on how the post-1787 democratic triumph prioritized individualism and equality over classical republican complexity, leading to a degenerated political discourse in the 19th century onward. In Creation, Wood laments this cost (e.g., the loss of virtue-based politics), and how this shift enabled liberal capitalism at the expense of richer civic republican traditions.

Leave a comment