INTRODUCTION ON BLACK AMERICAN RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE FROM NEW WORLD TO NEW THOUGHT

In a recent article about the concept of “Divine Messengers” in Islam and Theosophy, one of the key points I wanted to guide you into considering there are many influences that underlie modern understandings of religion, esotericism and theological study in the West, and in particularly the American experience. The esoteric definition of religion Blavatsky, Mazzini and Jamal al-Din advance is in distinction to “dogma.” A number of Christians have critiqued theosophists in contributing to this distinction and use of the word dogma and dogmatic to attack “established Christianity,” or “orthodox Christianity.” Any seminary student or layman that engages with theological defenses have developed a means to disarm this, and what still seemed in the nineteenth-century to be a radical and controversial distinction, despite the Protestant Reformation.

When you read my article about Maurice Joly, an early “New World” religion, Santeria was mentioned in connection to the Russian Yuliana Glinka as her main interest. Santeria, Yoruba and Vodun comprise a few African Traditional Religions as types of expression of religion since the very first African came to the New World. We, as Black people have tried to make sense of our experiences and understanding of self; and finding inspiration and knowledge that would shape our bodies, minds and culture. This is mostly based upon answers to the question, “What does it mean to be of African descent in a world dominated by White supremacy?” It is within this context that Marcus Garvey emerges and those influenced by him (e.g., Malcolm X’s parents), and Marcus Garvey’s early teachings and philosophy were in turn influenced by Noble Drew Ali, who founded the early twentieth-century Moorish Science Temple of America.

There have been some inaccurate ideas spread about the connection between H. P. Blavatsky (1831–1891), Jamal al-Din (1838–1897), Islamic esotericism and Noble Drew Ali (1886–1929), which this article specifically addresses. One of the main problems that negatively affected Black American social and religious movements, among Black Americans is that it is overburdened by a history of quackery. Also, brought on by overpromises from individuals who sought to construct new identities and place themselves within this history as Moses-like guides, prophets and luminaries. Black people are highly skeptical of such attempts by figures among us, even more than the theories which attribute all our ills to sabotage from external forces in business, society, politics, police and surveillance intelligence.

Despite the majority demography of Christian Black Americans, there is among us a very high skepticism of potential quacks, that sometimes contradict the faith and suspension of judgement placed in the authority of Christian pastors and priests. Despite this, there is indeed a history of esotericism in “African American” religious experience rooted in an exploration and explanation of the spiritual and the astral.

The writings of Black new religious movements are not merely met with skepticism by say, the White general populace, because Black people are very skeptical of Cleo-type figures, which Noble Drew Ali as Timothy or Thomas Drew represented, but this skepticism is partly a gradual development, partly a result of the failure (or dissatisfaction with results from Black new religious movements), and partly Christian defense against religious frauds, constructed new identities distorting the Bible, spiritualism and spiritual claimants. This is despite the fact, that elements of Spiritualism exist in the history of African Religious Tradition and Christian Black American beliefs.

MYTH-MAKING

I was going through many of my collected books on Scribd and related to one of them was a pdf from Willie Johnson called the Moorish Holy Temple of Science of The World. The writer made several claims, that are inaccurate.

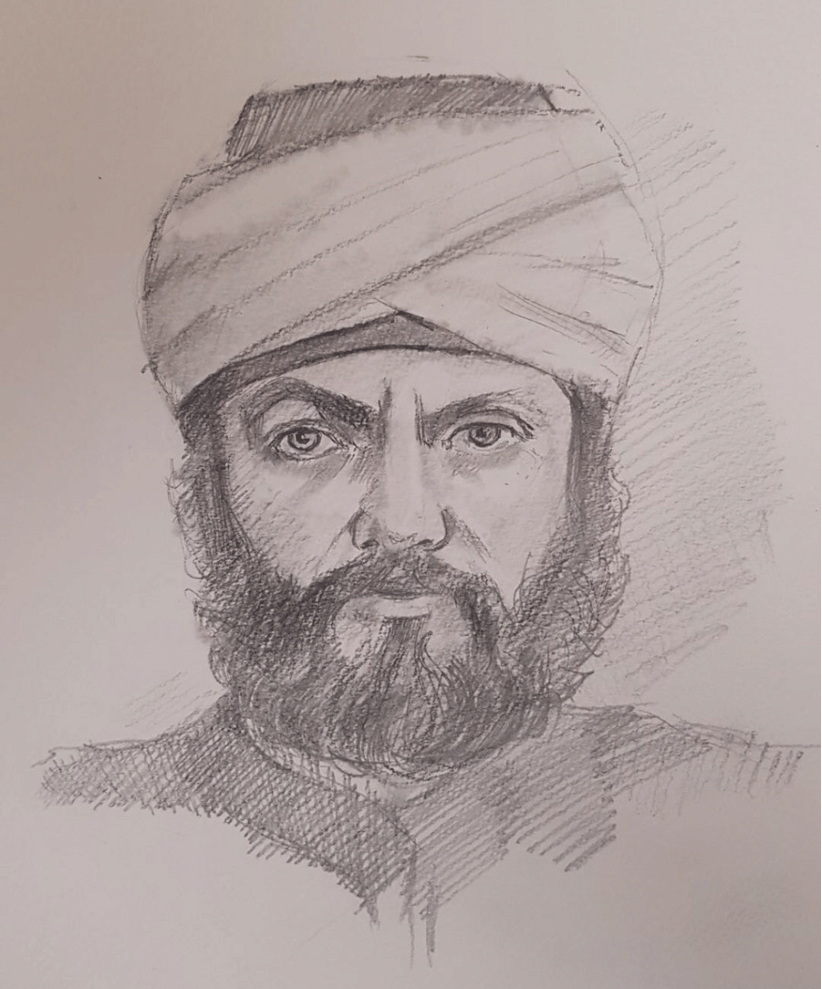

Sayyid Jamāl-al-Dīn al-Afghānī ud Din Bey Effendi [1838-1897]. He was a Pan-Islamist, a Master Adept, a Sufi scholar and teacher, a Muslim politician and a journalist. He founded a Masonic lodge, the Eastern Star. In Egypt during the mid 1800s Madame Blavatsky met and was taught by Jamal ad-Din al-Afghan, who she refers to a “Serapis Bey” one of the “Secret Chiefs”, or “Ascended Masters”, (others were “Morya” [Paschal Beverly Randolph], “Tuitit Bey,” “Koot Hoomi” and “Hilarion”, all pseudonyms, who purportedly belonged to the “The Asiatic Brethren” or “The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor,” who were aiding humanity to evolve into a race of supermen. The Master Adept Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani turned up in America around the winter of 1882-1883. Al-Afghani is said to have been joined by his disciple chief initiate, Mohammed Abduh.

The two missionaries had come to the United States to propagate the doctrine of ancestral and cultural pride under the banner of Pan Islam, which is meant to insure that the divine teaching of the ancestors are not forgotten among the Moors of North America (Amexem). It is said the Moorish National Divine Movement was founded on these teachings (Sufism) by Prophet noble Drew Ali. Eliza Turner and John Drew Quitman studied under Jamal al-Afghani, who were the parents of the man who would one day establish (M.H.T.S.) Moorish Holy Temple of Science / (M.S.T.A.) Moorish Science Temple of America and etc… At the hand of Jamal al-Afghani, the Drew family was inducted into the “sacred order”, known as “The Asiatic Brethren” or “The Brethen of Purity” brotherhood or “The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor.” In his early teenage years of Timothy Drew traveled to Egypt and study among the great “neophytes,” of Jamal al-Afghani and Muhammad Abduh.

While at Alzhar University, Drew Ali came under the influence of Mohammed Rashid Ridi (1865-1935) and Aziz al-Masri Bey (1878-1965), as well as the great Egyptian nationalist Duse Mohamed Ali-Effendi (1866-1945) who lived in London, England at the me. Drew Ali is said to have studied at the old Ethiopian College in Va can City (Rome, Italy). (Willie Johnson, Moorish Holy Temple of Science of The World)

My god. . . .

Sayyid Jamāl al-Dīn and Alleged Connections to Esoteric and Moorish Movements

This narrative links nineteenth-century Islamic reformer Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī (c. 1838–1897) to Freemasonry, Theosophy, and the early twentieth-century Moorish Science Temple of America. It portrays him as a “Master Adept” influencing H. P. Blavatsky and Noble Drew Ali. Willie Johnson of the Moorish Holy Temple of Science of the World relies on unverified myths, chronological errors, and unsubstantiated associations. I have to lay out some established points in the historical timeline.

While it is true Jamal al-Din was a pan-Islamist intellectual, journalist, and political agitator who traveled widely in the Muslim world and Europe to advocate Islamic unity against colonialism, the transatlantic connections alleged by Willie Johnson lacks credible evidence.

Jamal al-Din also did not establish a Masonic Lodge called the Eastern Star.

The Order of the Eastern Star was a Masonic appendant body for women and men founded in the United States in 1850 by American Freemason and educator Rob Morris (1818–1888), not Jamal al-Din. It drew from biblical heroines and was formalized in 1873 under the Grand Chapter of the Masonic Fraternity. Jamal al-Din had no primary or secondary involvement in its creation or operations, which were entirely American, thus predating his documented Masonic activities. While Jamal al-Din did join and possibly lead political intrigue within Egyptian Masonic lodges (e.g., Italian and British-affiliated ones in Cairo during 1871–1879) to oppose British influence, these were merely tools for anti-colonial agitation, not the founding of new orders like the Eastern Star.

There is another claim, that in mid-1800s Egypt, H. P. Blavatsky met and was taught by Jamal al-Din, who is portrayed as being “Serapis Bey,” a “Secret Chief” or “Ascended Master” from the “Asiatic Brethren” or “Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor.” Morya is portrayed falsely as being Paschal Beverly Randolph! Also, “Ascended Masters” is not a concept of H.P. Blavatsky. Paschal Beverly Randolph taught sex magic, which is in direct contradiction to their instructions and occult teachings. “Tuitit Bey” is also falsely portrayed as both Koot Hoomi and Hilarion.

Blavatsky (1831–1891) visited Egypt around 1870–1872, overlapping briefly with Jamal al-Din’s residence there between 1871 and 1879. However, no contemporary records such as diaries, letters, or eyewitness accounts confirm they met or that he taught her. The identification of Jamal al-Din as Serapis Bey originates from speculative modern conjecture, such as K. Paul Johnson’s book The Masters Revealed (1994), which hypothesized that Blavatsky’s masters were real historical figures she networked with and covered their identities under pseudonyms to protect an operation connected to the Great Game. The Great Game is described as “a rivalry between the nineteenth-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet.”

As stated, this is conjecture, not concrete evidence. Johnson himself noted the lack of direct proof. Concerning the affairs of American occultist Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825–1875), there is no indication of Jamal al-Din’s involvement.

The “Asiatic Brethren” referenced in the work as the Fratres Lucis (or Brotherhood of Light) was an eighteenth to nineteenth-century European Rosicrucian-Masonic group that expressed a hybridism of Jewish Kabbalism and Christian esotericism. The group was active among German and Eastern European elites, and not a Muslim or Egyptian order that Jamal al-Din led. The “Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor” (HBL) was a late-nineteenth-century Anglo-American occult society publicized in 1894 and focused on practical magic and sexual mysticism. It was founded by Thomas Dalton and Peter Davidson, with no credible or documented connections to Jamal al-Din. Sources inaccurately draw ties between Blavatsky’s Cairo networks, but as can be seen, this is not historical, but engagement in post-hoc mythmaking within the Black alternative religious milieu of Moorish lore.

Another claim made is that Jamal al-Din visited America in Winter 1882–1883 with disciple Mohammed Abduh to promote pan-Islamic ideals among the “Moors of North America (Amexem)” for ancestral pride.

However, Jamal al-Din’s well-documented travels place him in India (1880–1882), then London (early 1883), and Paris (mid-1883 onward), where he published the pan-Islamic journal al-Urwah al-Wuthqa with Abduh (1849–1905). Biographies from scholars like Nikki Keddie and Britannica do not document any visit to the U.S. Jamal al-Din focused on Muslim and European audiences against British imperialism. Abduh, his prominent disciple, remained in Egypt until his 1884 exile, and never traveled to America. The “Moors of Amexem” (a MSTA term for African Americans as ancient Moabites or Moors) is a twentieth–century construct by Noble Drew Ali (1886–1929), with no nineteenth-century pan-Islamic mission to North America. This claim echoes unsubstantiated Moorish lore, with no historical records.

The Moorish National Divine Movement was not founded on Jamal Al-Din’s teachings or Sufism by Noble Drew Ali. The MSTA, founded by Drew Ali in Newark, New Jersey (around 1913–1925) blended Black nationalism, Freemasonry, Christianity, and a conception of Islam emphasizing African Americans as “Moors” from the “Moroccan Empire.” Influences included the mentioned Marcus Garvey’s UNIA, Ahmadiyya Islam, and possibly earlier groups like the Moorish Hebrews or Abdul Hamid Suleiman’s Canaanite Temple, although with no direct Sufi or lineage to Jamal al-Din’s teachings on religion and philosophy.

Jamal al-Din’s pan-Islamic ideals were modernist and anti-colonial, not Sufi, even critiquing some Sufi orders as superstitious. MSTA texts like The Holy Koran of the Moorish Science Temple (1927) drew directly from works such as The Aquarian Gospel, not Jamal al-Din’s writings. Scholarly analyses (e.g., in Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Religion) trace MSTA to early twentieth-century U.S. new Black religious innovations, and not nineteenth-century Persian-Afghan reformism.

There is also no evidence, that the persons Eliza Turner and John Drew Quitman studied under Jamal al-Din. It is stated that they were parents of the MSTA founder, who established the Moorish Holy Temple of Science (M.H.T.S.) or Moorish Science Temple of America (M.S.T.A.). Drew Ali’s birth name was likely Timothy or Thomas Drew born January 8, 1886, in North Carolina, and died in 1929. His early life was often shrouded in legend, though official records show him as a U.S.-born laborer using “Drew” consistently, until adopting “Noble” in the 1910s. His teachings expressed the New Thought milieu, and he donned an outfit similar to a wizard in the streets. Some MSTA-affiliated sources claim parents Eliza Turner-Quitman (of Washitaw-Tunica heritage) and John A. Drew-Quitman (a Cherokee leader), but these are unverified genealogical myths, absent from census data, vital records, or neutral biographies.

John A. Quitman (1798–1858) was however a real historical figure, who served as a Mississippi politician and filibuster who died 28 years before Drew’s birth. This makes any connection to John A. Quitman impossible. No evidence places these supposed parents in Egypt or under Jamal al-Din’s tutelage. Drew Ali founded the Canaanite Temple (1913) and MSTA, but without familial Masonic or Islamic scholarly lineage.

Then, how can it be said that the Drew family was inducted by Jamal al-Din into the “Sacred Order” of the “Asiatic Brethren,” “Brethren of Purity,” or “Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor,” when they teach contrary doctrines. The Asiatic Brethren was a defunct eighteenth-century European esoteric Masonic group, and the HBL a nineteenth-century Western occult order, with neither involving the Drew family (American, early twentieth-century). The “Brethren of Purity” (Ikhwan al-Safa) was a tenth-century clandestine Ismaili group of scholars in Basra, known for their philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, the Rasa’il al-Ikhwan al-Safa, not a modern brotherhood Jamal al-Din led. Jamal al-Din’s Masonic ties were for a political reason in Egypt (1870s) according to Muhammad Abduh, not esoteric initiations for American families. The “Sacred Order” his Drew Ali’s family were said to be initiated into has no primary evidence.

Early Teenage Years, Timothy Drew Travels to Egypt to Study Among “Neophytes” of JAMAL AL-DIN and Muhammad Abduh at Al-Azhar University

Can Drew Ali’s travels to Egypt to study as a neophyte of Jamal al-Din and Muhammad Abduh at Al-Azhar University be verified, as Willie Johnson claims? Drew Ali was born in 1886, putting his early teens c. 1899 to 1903. Jamal-al-Din died in 1897 in Istanbul, ending any claim of possible direct study. Abduh died in 1905 and taught at Al-Azhar (Cairo’s premier Sunni seminary), but Abduh focused on Egyptian reform, with no records mentioning any American teenager as his pupil. MSTA hagiography claims Drew’s Egyptian and Moroccan travels involved divine revelation, but this is evident constructed lore and is most likely inspired by his own study. There exist no traces of enrollment for Drew at Al-Azhar.

At Al-Azhar, it is further claimed that Drew Ali was influenced by Mohammed Rashid Rida (1865–1935), Aziz al-Masri Bey (1878–1965), and Duse Mohamed Ali-Effendi (1866–1945) who lived in London.

These were Egyptian and Arab nationalists. Rida was a Salafi journalist, al-Masri Bey was a military officer, and Ali-Effendi was a pan-Africanist publisher of The African Times and Orient Review in London (1912–1920). Drew Ali could have encountered and absorbed their ideas through U.S. immigrant networks or publications in the 1910s–1920s, given that MSTA echoed pan-African themes. Drew’s literacy and influences were likely domestic influences through Chicago’s Black press. Rida and al-Masri were contemporaries, but not neophytes of Jamal al-Din in the 1900s. Ali-Effendi was based in London after 1911, and after Jamal al-Din’s death.

The other unsubstantiated claim is that Drew Ali studied at the “Old Ethiopian College” in Vatican City (Rome, Italy). So, the Pontifical Ethiopian College existed as training for Ethiopian Catholic clergy and traces an informal root to fifteenth-century pilgrim hospices. The Pontifical Ethiopian College was formally established in 1919 by Pope Benedict XV inside Vatican walls. Drew Ali’s alleged early studies before 1905 predate this. Even the prior informal hospice wasn’t a “college” for non-Ethiopian lay students. Additionally, there are no records that connect him to Rome, and his biography shows U.S.-based activity from childhood. This appears therefore as ahistorical embellishment.

While Jamal al-Din’s historical legacy as a pan-Islamic reformer influenced modernist and global Muslim thought, the narrative fabricates a connection between Theosophy, Drew Ali and Moorish Science Temple of America through conflicting timelines (e.g., post-1897 interactions) and unproven speculations. These claims thrive on the internet and in old pamphlet lore, but collapse under scrutiny from archives, biographies, and comparison of timelines.

The entire issue is something I think is important to learn about, among problematic patterns following from the seventeenth-century into the twentieth-century that new efforts should avoid engaging in. Already, within the study of esotericism and classical philosophy, we need better representation, but also credibility, diligent researchers and respect.

This can even be achieved in the development of new genuine philosophy and movements: i) not focused on constructed authoritative and inventive narratives about our life history; ii) neither on employment of anonymity and pseudonyms over openness and honesty; or iii) racial jealousies or animosities that limit and frame construction of identity within a world “dominated” by how White racists view the World. Even the attempts at developing philosophies of strength and racial pride are limited to this framing, or by placing ourselves within the histories of other people’s identities. As I have always stated however, religion does not need to be factual or true to spread, and unfortunately many certain ideas and groups have spread and competed for their influence on the minds of Black Americans.

Nikki Keddie’s Sayyid Jamal ad-Din “al-Afghani”: A Political Biography (1972) and Jacob Dorman’s Chosen People: The Rise of American Black Israelite Religions (2013) goes more in depth about the history, while Esotericism in African American Religious Experience (2024) and Niels Lee’s Islam Near the Turn of the Century: Jamal al-Din and Religious Paradox (2024) helped to understand Jamal al-Din’s ideas and their context.

Leave a comment