EARLY BLACK INTELLECTUALS AND THE INFLUENCE OF CLASSICISM AND REPUBLICANISM

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a small but influential group of Black intellectuals engaged deeply with Greco-Roman classics and the ideals of classical republicanism. This engagement was multifaceted in that they drew on ancient texts to demonstrate Black intellectual capacity in the face of racist denials. This challenged e.g., claims by Thomas Jefferson and David Hume that Africans were inherently inferior; to critique the hypocrisy of American slavery in a nation founded on republican principles of liberty, virtue, and equality; and to reconfigure republicanism itself as a tool for emancipation and anti-domination. Classical republicanism, rooted in Roman thinkers like Cicero and historical examples from the Roman Republic, emphasized civic virtue, freedom from arbitrary domination, and the common good — ideas that profoundly shaped the American Founding Fathers. Black thinkers adapted and studied these traditions finding in them the contradictions of a slaveholding republic to demand full inclusion.

This tradition, sometimes termed “Black republicanism” or “Classica Africana,” emerged despite severe barriers: enslavement, laws prohibiting Black education, and widespread beliefs in racial inferiority. Yet, through self-education, limited formal schooling, or patronage, these intellectuals mastered Latin, Greek, and classical rhetoric, using them as weapons in abolitionist discourse. This history places itself within the story and heritage within a global context. A rebuttal against accusations of modern Black radical politics being grounded in Marxism or Communism does not count, if Black Americans themselves do not really understand the roots of these revolutionary notions; and to not use them merely as weapons, or rather shields for civil rights, but learn it, study it as they studied it closely, embody and profess this strong political (once divine) philosophy and expression that cannot be denied without the system completely collapsing from within.

We will not allow this, because there are some among us that will and must take up this tradition in its fullness. When I write or speak of Republicanism, I do not mean some particular “niche” political theory, or focusing it through the special interpretation of a singular figure, or some particular single political party (e.g., the history of “The Switch” in U.S. Politics) — I mean it in its historical fullness, without any dilution of its classical and even “sacred” lineage. The latter is part of a long history of inter and transcultural dialogue of religion, political theory, science, theology and philosophy that has been lost and in a way — cut off from the modern thinker, except through fragments. The habit and idea of expecting and waiting on other peoples to accept our place in this history is over. Do not demand, or beg. Take the tradition, represent it, lead and transform through the knowledge just like these early thinkers did. Then, you will find emerging among you organically, your New Renaissance. This takes effort. This takes new inspiration to generate new thinking. One definite way the early republican-minded knew to cause this was to return to their “old writers” and wisdom of their ancestors.

PRIMER ON A FEW IMPORTANT EARLY AMERICAN BLACK INFLUENCES

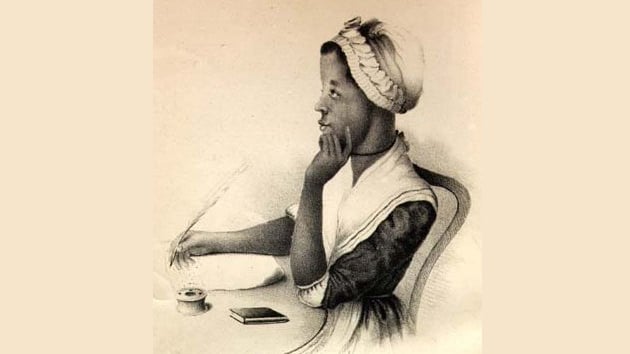

Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753–1784)

Phillis Wheatley, enslaved from childhood and brought to Boston, became the first African American to publish a book of poetry (Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, 1773). Her work is heavily steeped in neoclassical style, drawing heavily from Homer, Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Alexander Pope. She translated classical themes into English verse, often imitating heroic couplets and allusions to Greco-Roman mythology.

Wheatley’s classicism served a dual purpose: proving Black intellectual equality as her poetry was authenticated by a panel of White Bostonians to confirm a Black woman could author it; and subtly critiquing slavery. In poems like “To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth,” she invokes republican liberty while alluding to her own enslavement: “I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate / Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat.” Her ode to George Washington (Logos and Divine Providence in George Washington’s Faith) portrays him as a classical hero, reimagining “Columbia” (America) in neoclassical terms (see Columbia: American Minerva and the Fasces in Harper’s Weekly “Reconstruction” for Equal Rights, 1868), which contributed to later cultural icons like the Statue of Liberty.

Influenced by republican ideals of freedom, Wheatley connected American independence to abolition, asking in one poem how colonists could seek liberty while holding Africans in bondage. Her work exemplifies early Black use of classics to challenge domination, blending Christian providence with Roman stoicism and virtue.

Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806)

A free-born mathematician, astronomer, and surveyor, Banneker was largely self-taught, borrowing books on classics and science. His almanacs (1792–1797) included astronomical calculations rivaling those of his White contemporaries, implicitly refuting racial inferiority theories. Banneker’s most direct engagement came in his 1791 letter to Thomas Jefferson, enclosing an almanac manuscript. He invoked natural rights and republican equality, quoting the Declaration of Independence against Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, which claimed Black people lacked reason. Banneker drew on Biblical and historical parallels drawing on classical Republicanism’s emphasis on virtue and liberty from tyranny, urging Jefferson to emulate Roman emancipators. As a surveyor for Washington, D.C., Banneker helped lay out the capital — a neoclassical city inspired by Roman urban planning symbolizing his contribution to the Republic’s physical and ideological foundations.

Absalom Jones (1746–1818) and Richard Allen (1760–1831)

These founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church engaged classics through sermons and petitions. Jones’s 1808 thanksgiving sermon referenced ancient history and republican themes of deliverance, comparing Black suffering to Biblical Israel while invoking American revolutionary liberty.

Their 1794 petition against slavery drew on Enlightenment and republican rhetoric, emphasizing civic virtue and equality — ideas traceable to Cicero and Roman Republicanism.

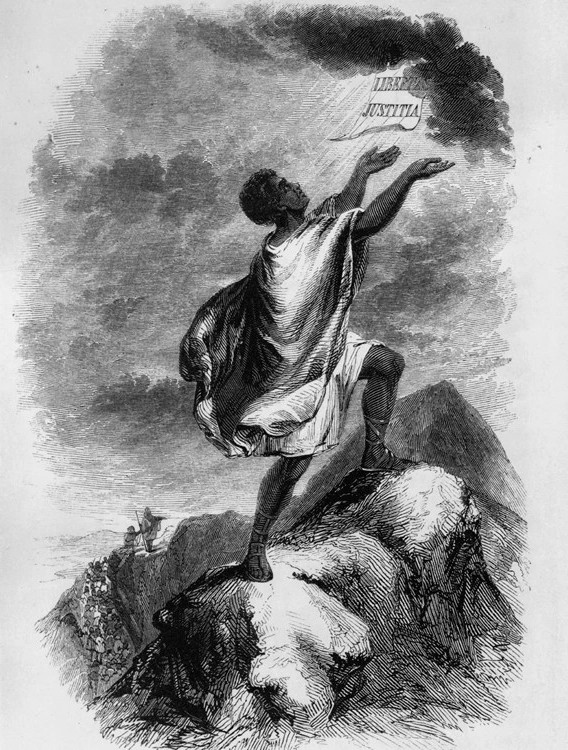

David Walker (1796–1830)

In his fiery Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829), Walker cited ancient history extensively: Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks as examples of Black achievement and the perils of tyranny. He referenced Haiti as a modern “glory of the blacks” like the ancient Republics, warning of divine retribution like the Fall of Rome.

Walker’s rhetoric were similar to classical oratory (e.g., Cicero’s invectives), calling for resistance against domination. He critiqued American Republicanism as hypocritical, demanding Black people claim the liberty promised in classical and revolutionary traditions.

Read more about David Walker and connections to pre-Socratic and ancient African tradition in Abolitionist David Walker turns Fire into Radical Revolution against Slaveholding Republic.

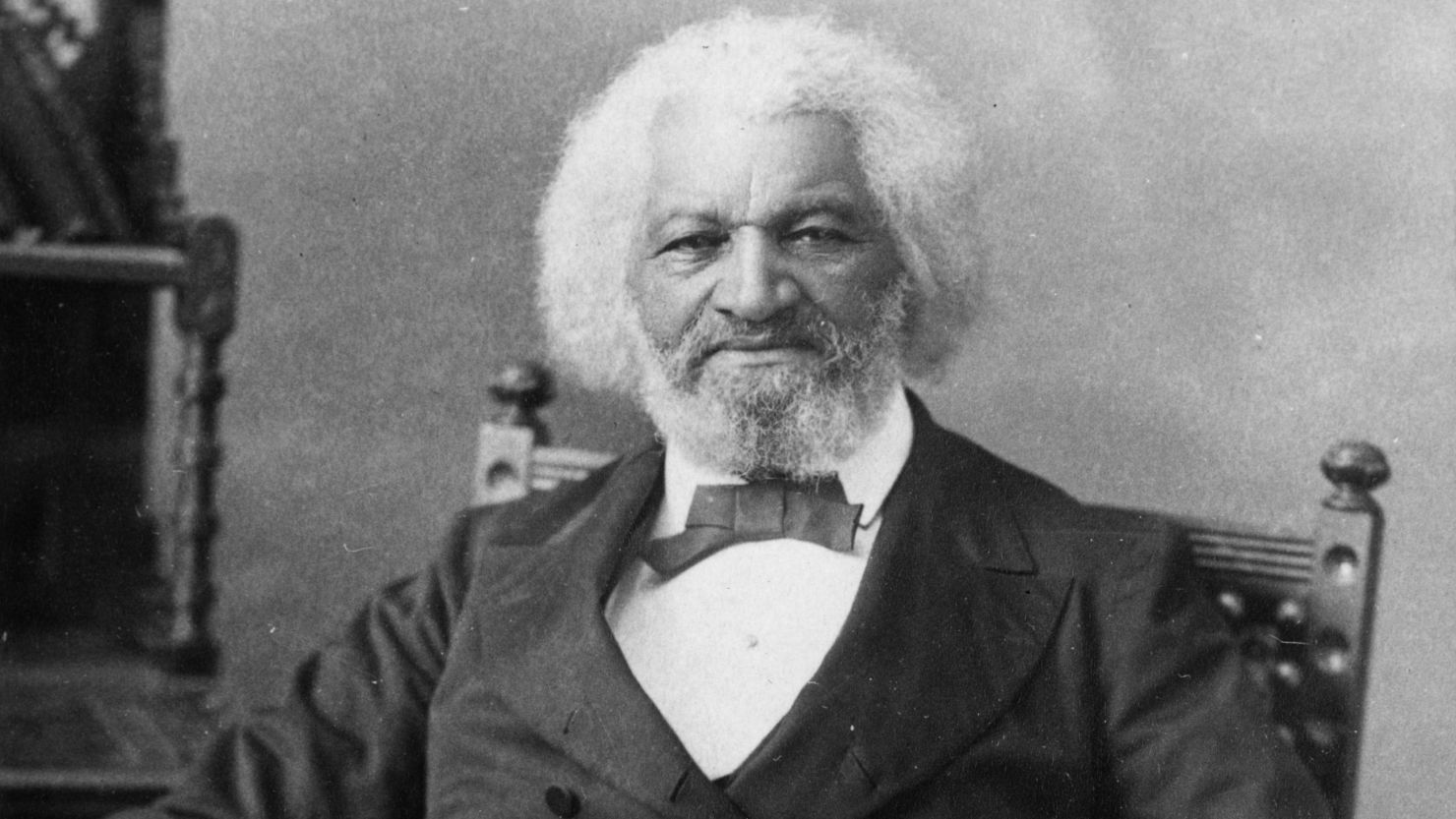

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895)

The most prominent, Douglass self-educated himself using The Columbian Orator, a staple text with speeches by Cicero and Cato defending Roman Republicanism. A dialogue on slavery in the book awakened his abolitionist consciousness, teaching him rhetorical tools from classical masters.

Douglass’s speeches and writings (Narrative of the Life, 1845; later autobiographies) invoked Roman heroes like Cato as a symbol of anti-tyranny and Scipio. He reconfigured republicanism into a radical anti-domination theory: freedom not just as absence of chains but as non-vulnerability to arbitrary power. As a “radical Republican,” Douglass demanded full Black citizenship, education, and integration, critiquing the Founders’ compromises on slavery as betrayals of classical virtue. His travels to Rome and Egypt deepened his use of classics to affirm Black humanity and ancient African contributions.

𓆝 𓆟 𓆞

LEGACY

These thinkers participated in a “Black Republicanism” as scholar Melvin Rogers termed it, reshaping 19th century republican theory amid slavery. From the 1830s–1850s, they exposed white supremacy’s contradictions, using classics to argue for freedom against domination. Classicism proved Black equality, by countering pro-slavery uses of Greece and Rome (e.g., slavery as “natural”) by highlighting ancient declines due to enslavement. This tradition continued into the 20th century with Black classicists like William Sanders Scarborough. These individuals prove how marginalized voices enriched American intellectual life, holding the nation accountable to its professed classical-republican ideals of liberty and virtue. The fullness of this heritage can today challenge limitations in modern political theory, theological dogmatic orientations, and materialist consumerist-slave culture to create and foster new culture and new ideas among Black Americans.

Leave a comment