Reflections tying classical worlds to Black American history and Douglass’s rhetorical strategy in engaging with classical antiquity and critiquing aspects of Catholic ceremonial from a republican, Protestant perspective.

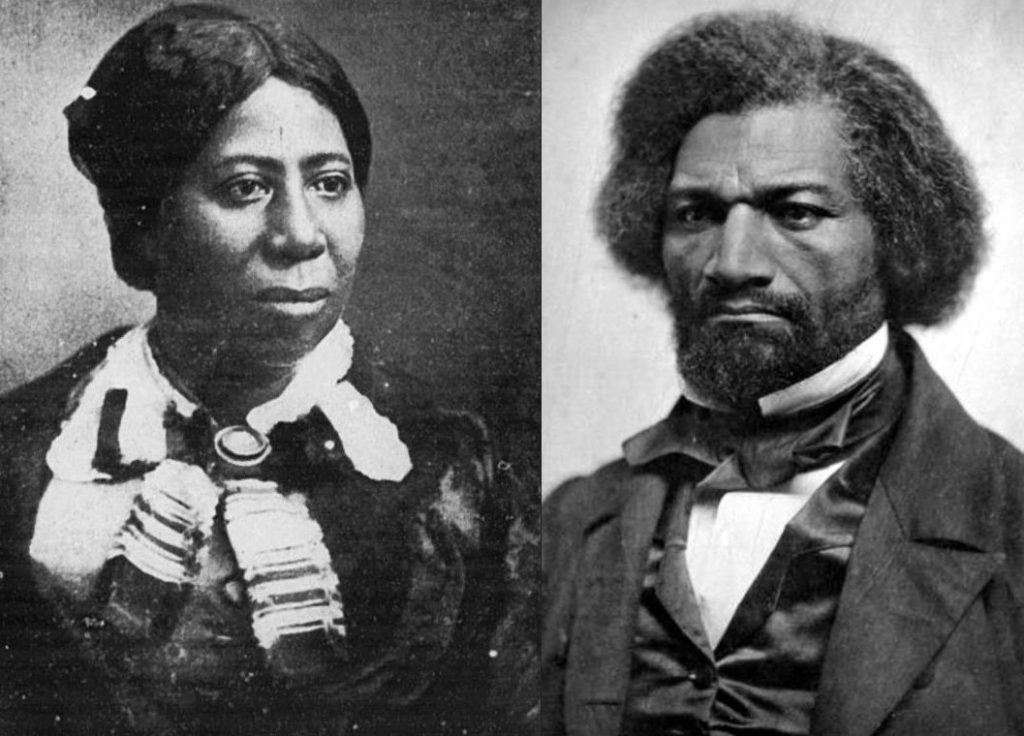

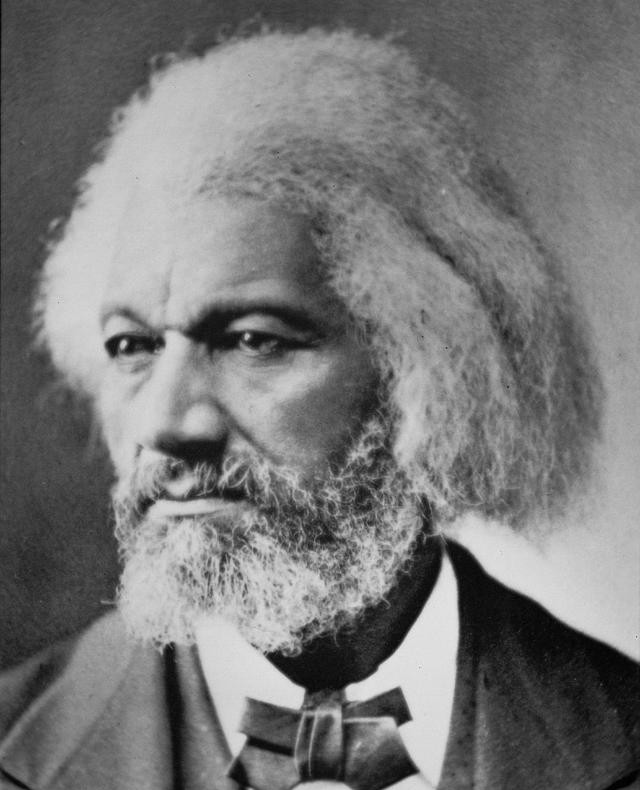

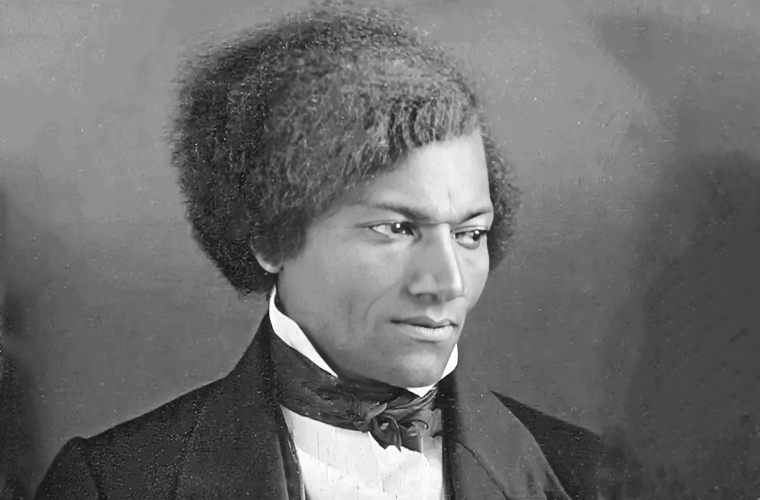

In the waning days of September 1886, Frederick Douglass, the abolitionist and statesman set sail from New York aboard the steamer City of Rome, beginning an extended tour of Europe and Egypt that lasted into 1887. Douglass’s tour covered England, Ireland, France, Italy, and Egypt (including Port Said, Cairo, Memphis, and Giza) during 1886-87. He was accompanied by his second wife, Helen Pitts Douglass, a white woman whose union with him had stirred fierce controversy in America. This voyage marked the beginning of an extended Grand Tour through Europe and the Mediterranean, lasting until August 1887. Douglass was at a prior point Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, a position bestowed upon him by President Grover Cleveland. This journey for him served as a restorative period from the relentless racial strife of the United States, and he found from his observations of Egyptian antiquity a means to contest racist claims that dismantle the pseudoscience of racial prejudice. Douglass chronicled the expedition in his private diary, now preserved at the Library of Congress, stirring public lectures upon his return. Other sources include the 1892 edition of his autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Helen, too, maintained her own journal, capturing intimate glimpses of their shared adventures.

Visit to Rome (January-February 1887)

Douglass described Rome as overwhelming in its historical density and grandeur, with awe at its antiquity with ambivalence toward Catholic splendor. Douglass sailed in mid‑September 1886 on the steamer City of Rome with Helen Pitts and kept a travel diary for the 1886–87 tour now held at the Library of Congress. The tour included England, France, Italy, and Egypt (Port Said, Cairo, Memphis, Giza) in early 1887. He returned to Rome in spring and January 19, 1887. His diary records Rome visits in January and later with a week‑long stay to January 27 and later return. The diary and later writings record arrival at Port Said in February 1887. Douglass used the trip in lectures (e.g., My Foreign Travels) and expanded reflections appear in the 1892 edition of Life and Times.

On the evening of January 19, 1887, after traversing the sun-drenched landscapes of southern France and northern Italy, Frederick and Helen Douglass alighted in Rome. They lodged initially for about a week, until January 27, before pressing onward to Naples. Yet the Eternal City’s allure drew them back in the spring for a deeper immersion. Douglass’s 1886-87 diary records his intense response to the city’s layered history and art, and his published reflections from the tour describe both the ancient pagan monuments and the wealth of the Vatican collections. The city’s ancient pagan splendor, with its crumbling forums, towering obelisks looted from distant Egypt, and the vast amphitheater where gladiators once clashed and animals fought in brutal spectacles, stood in stark contrast to the lavish Vatican and the Catholic Church’s gilded dominion. As a Protestant steeped in American republicanism, Douglass critiqued this ecclesiastical opulence as decadent and antithetical to democratic virtues. Still, he marveled at the sheer scope of human ingenuity across the ages. Douglass wandered the grounds of St. Peter’s Basilica, explored the Vatican, and trod the stones of the Roman Forum. His path likely led him to reflect on Rome’s imperial glory and decay. Rome’s stratified history, from the Caesars’ empire to the popes’ theocracy, resonated with Douglass’s lifelong reverence for classical ideals of liberty and civic virtue, which he had invoked in his orations against slavery. In this ancient cradle, he forged parallels to his own battles for equality.

As scholar Robert S. Levine elucidates in his essay Road to Africa: Frederick Douglass’s Rome, published in African American Review in 2000, Douglass fashioned himself as a refined, erudite Black voyager. He likely inverted the conventional narratives of White American tourists, who often viewed Europe through only a lens of cultural superiority to African civilizations. Instead, Douglass confronted the excesses of Catholicism while embracing classical antiquity as a shared human inheritance, one that bridged to his impending sojourn in Egypt. This perspective allowed him to claim a place among the civilized elite, challenging the racial hierarchies that dogged him at home. This was a time for African American expatriates, like the abolitionist Sarah Parker Remond, who had made Italy her home after fleeing American prejudice. She was living in Rome, married to an Italian man (Lazzaro Pintor), and was part of an elite intellectual circle. Douglass’s time in Italy allowed him to reflect on the global context of the abolitionist movement. This history details resilient networks of solidarity in the transatlantic system with the awareness of shared struggles against oppression, which enabled many abolitionists to find common ground.

Visit to Egypt (February-March 1887)

Douglass reflected on Egyptian antiquity to challenge racist narratives. Douglass’s 1886–87 travel diary and his later Life and Times include descriptions of Cairo, the Nile, Memphis, the Pyramids of Giza, and the Sphinx. He records climbing the Great Pyramid and remarks on the experience and the monuments’ power to refute claims of Black inferiority.

From the shores of Naples, the Douglasses departed Italy on February 12, 1887, aboard the steamer Ormuz. Four days later, on February 16, they docked at Port Said, the gateway to Egypt’s wonders. Venturing southward along the Nile, they explored Cairo’s bustling streets, the ancient ruins of Memphis, and the timeless Pyramids of Giza. This leg of the journey held profound ethnological significance for Douglass, who had long combated assertions of Black intellectual inferiority, such as those penned by Thomas Jefferson in his Notes on the State of Virginia. Egypt offered tangible proof of Africa’s ancient grandeur, countering racist doctrines that severed Black people from civilization’s origins. In Life and Times, Douglass reflected on the Egyptian populace: “I do not know of what color and features the ancient Egyptians were, but the great mass of the people I have yet seen would in America be classified as mulattoes and negroes.” He visited the Great Pyramid of Cheops, with its massive stones — a testament to the engineering prowess predating European empires. Gazing upon the Sphinx, he argued that Egyptian achievements challenge racist assumptions, finding Africa’s foundational role in human progress. Douglass lingered in Egypt for several weeks, attending a Sunday school at the United Presbyterian Church Mission in Cairo on February 20, where he spoke to a gathering of children with words of encouragement.

Douglass drew contrasts among ancient Egyptian religion, Roman Catholic ritual, and the forms of Islam he observed in Egypt. Douglass admired aspects of Muslim worship he saw, especially communal equality in prayer. We can draw from this contrasts with the U.S. history of race practices and America’s segregated pews. As contemporary readers, we can imagine moments he might have had, that show how social status and race differed or related abroad. Douglass argued that Egyptian antiquity complicated racist histories, and the idea that Egypt’s splendor challenged claims that Black contributions to history were negligible has been the angle of some African scholars. From this, many scholars have written of the antiquity of Africa, contributions and shared ideas underlying particular Greek and Roman religio-philosophical foundations. Through Rome’s republic and Egypt’s African majesty, Douglass’s travels shaped his classical allusions in the fight for Black equality. The Tour not only refreshed his spirit but armed him with strong evidence he used rhetorically to support his vision of a shared human legacy, and one that transcended the narrow prejudices of his era.

REFERENCES

- Frederick Douglass, Life and times of Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Boston: De Wolfe & Fiske Co., 1892; see Chapters 50-51.

- Frederick Douglass, “My Foreign Travels (Part 2).” Lecture, December 1887. Frederick Douglass Papers Project, University of Rochester.

- Lucinda Hinsdale Stone, Lucinda Hinsdale Stone: Her Life Story and Reminiscences. Edited by Belle McArthur Perry. Detroit: Blinn & Smith, 1902, Pdf.

- Robert S. Levine, “Road to Africa: Frederick Douglass’s Rome,” African American Review 34.2 (2000): 217–31.

- Margaret Malamud, African Americans and the Classics: Antiquity, Abolition and Activism (2016).

- Gary Totten, Frederick Douglass in Context: Tour of Europe and Egypt, Chapter 5, Cambridge UP, 2021.

Leave a comment