The Meaning OF Illuminati and WEISHAUPT’S IdeaS ON ENLIGHTENMENT REASON AND MORAL ORDER

There are solely two relations or meanings to the term ILLUMINATI we permit as authentic:

- It is a collective term applied to ancient oracular philosophers, magi, adepts (e.g., Zoroaster) with possible extension to neo-Mazdean mythical Iranian prophets (or sages).

- Johann Adam Weishaupt’s German Bavarian Order of Illuminati, as a counter-Jesuit organization for spreading not merely the Enlightenment ideas (Church as primary source of legitimacy in ideas and authority), but the spirit of the ideas that have been transmitted through periods into the Enlightenment. This history is part of the history of REPUBLICANISM. Thomas Jefferson recognized the circumstances in which Weishaupt lived, and Jefferson understood that if Weishaupt had lived in Philadelphia, he would have been free to write the things he did and not resort to his games of secrecy as his means. Weishaupt himself of course fell out of favor with this method in his period of exile.

Although, it can be said, that the Illuminati got their name from European sources, and not directly from Zoroastrianism or Manichean dualism, this is a surface-level understanding about the term itself, and even the historical order of that name. The Illuminati is a failed organization limited by the context of its time, with very particular opinions about views of nature, human nature, enlightenment science (e.g., psychology and physiognomy in determining character), society, gender-roles and hierarchy. Weishaupt’s ideas for his order were hierarchical, despite being critical of hierarchy in politics and government; and the cause of his order in his view represents an anarchist utopian fellowship of society as a family, critical of nationalism and private property.

WEISHAUPT ON EARLY CHRISTIAN USAGE OF THE TERM ILLUMINATI

The term in reference to “illuminated ones” however has classical roots, particularly of ancient Persian (Iranian, or Aryan) influence in reference to Magism, and in the “Western” so-called context, blends with German Christian (Protestant) Perfectionist notions. Adam Weishaupt was not directly inspired by the Avesta, but the influence may be attributable through Anquetil-Duperron’s emerging translations of the Avesta, Jesuit missionary reports and general eighteenth-century European fascination with Persia. He explains that the name of the Illuminati stems from the earliest church. He mentions this in the section justification for the order’s name (Rechtfertigung des Ordensnamens) in Einige Originalschriften des Illuminatenordens (the Bavarian government’s official publication of seized Illuminati documents in Munich, 1787, pp. 229–230).

It is explained by Weishaupt in these German documents that was reorganized by the Bavarian government, the name “Illuminati” was not invented by him, and that it had been used in the earliest Christian communities to refer to the “enlightened” or “illumined,” or those who had received deeper instruction and the fire of wisdom through spiritual baptism (i.e., initiation). Thus, Weishaupt defended the choice of the name “Illuminaten” by pointing to earlier historical and religious uses of the term illuminati or illuminés. Working within a Christian framework, this was his attempt to counter accusations against his order as occult, demonstrating that the name was respectable, ancient, and appropriate for a society dedicated to moral and intellectual enlightenment.

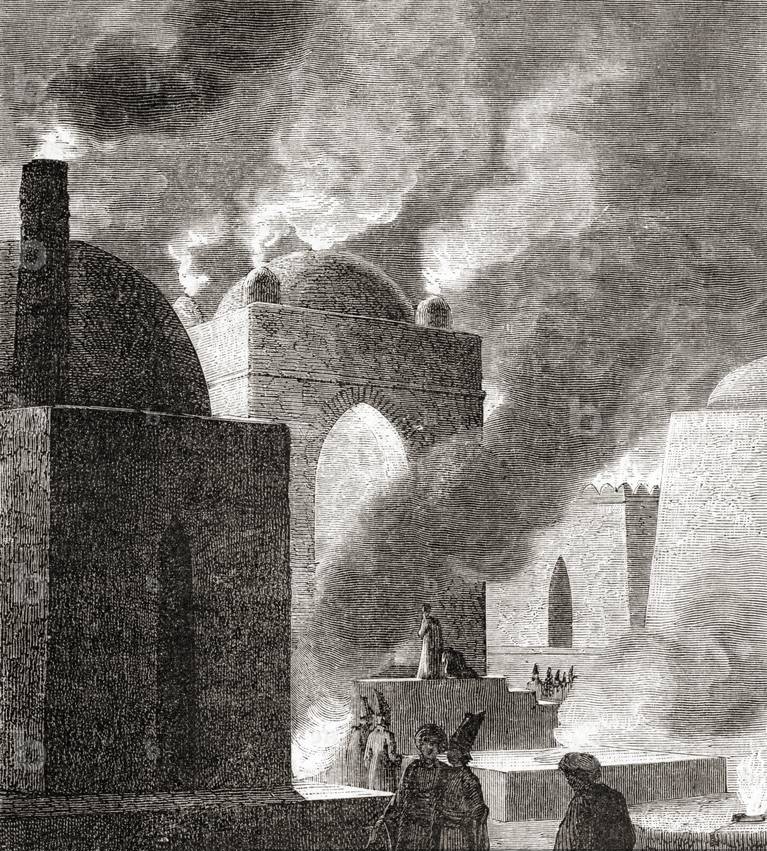

SYMBOLISM OF FIRE AND LIGHT IN ILLUMINATI ALLEGORY

I have discussed FIRE a great deal as of late. What is FIRE to the ancient philosophers?

Weishaupt chose the Magi, the priestly caste of ancient Persia and their fire symbolism as the model in his order, which shows that he is merely using Magian and Biblical symbolism in the same way Freemasonry use Biblical and Hermetic symbolism.

FIRE, in Zoroastrianism, represents purity, truth, and divine presence, making it a fitting allegory for Weishaupt’s idea of the Perfectibilists, or the moral and philosophical aims in the order’s advanced teachings. I do not believe Weishaupt possessed such “advanced teachings,” though it does not refute the truth underlying the basis of his ideas. We understand, that Weishaupt has an Enlightenment-era style of esoteric pedagogy within his social and societal circumstances, carrying ideas threatening to the monarchical order of his Bavarian government.

CIVILIZATIONAL EMBODIMENT OF METAPHYSICAL DARKNESS

The Avesta’s translations into European languages had an influence on many eighteenth-century European thinkers. There is also a linguistic similarity to ishraq. I am referring to the Illuminationist (Ishrāqi) philosophical school of the murdered Persian master, Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi (1154–1191), a reviver of the philosophy of the Iranian sages. In observing the way these terms are used in popular culture: occult, light, illuminati, enlightenment, illumination, it demonstrates the condition the civilization finds itself in as representing a character and love of haughtiness, ignorance and selfishness.

MARTIAL ETHICS VS RATIONAL VIRTUE VS GNOSIS BEYOND REASON

The history and ideas discussed reflect a very long and cherished historical development from ancient symbolic theology moving into and shaping modern secular humanism, mediated by medieval synthesis of reason and intuition. This shows a time of transition from an age of martial and heroic ethics in antiquity to enlightened subversion in modernity, but ours exist in a way in which Suhrawardi’s ideas of mystical ascent serve as a bridge. In all three systems, Light, or Fire serves as a core metaphor for truth, creation, and enlightenment, but their relation to being and application vary significantly. The purpose of analyzing the three is to dismantle illusions of cultural barriers.

The Avesta, the sacred scripture of Zoroastrianism emphasizes the same things vital to the theosophist of every country as a mythic and practical template equivalent to Weishaupt’s Enlightenment era emphasis on moral improvement, rational virtue, and symbolic initiation.

What does this basis contain:

✅ The moral purification of the individual

✅ The sacredness of fire

✅ The cosmic struggle between truth and falsehood

Suhrawardi’s Ḥikmat al‑Ishrāq (“Wisdom of Illumination”) builds directly upon this through an Aristotelian and Neoplatonic-Islamic framework, rather than Avestan theology. In this idea, moral and spiritual progress is an ascent through degrees of light, purifying the soul so it can receive stronger illumination. For Weishaupt, fire is the emblem of intellectual-moral enlightenment. For Weishaupt, the meaning of illumination is republican and metaphorical. Rooted in his rationalist beginnings, reason is the liberator of humanity from religious and monarchical tyranny. Illumination, in the context he uses it is achieved through education, critique, and secret dissemination of knowledge. Although for Weishaupt, this meant the aim for moral and social perfection through rational reform, there were others in his order like Knigge that interpreted it theosophically. Weishaupt therefore engages in a habit I have observed between the Renaissance to the Secular Enlightenment; and this habit is in secularizing ancient philosophical concepts, e.g., light and transforming it from a sacred symbol to an idea for social and political reform.

For the esotericist, for the ancient philosophers his ideas principally derive from, they reference fire as the primordial principle and origin of the mind and world. Light, taught Suhrawardi is the very fabric of being and knowing. Light (Nur) is the fundamental being of reality, composed of a hierarchy emanating from the Light of Lights, Allah who is Light of the heavens. Everything exists as degrees of light intensity, and true knowledge is when the knower is illuminated by the known. Therefore, light is not merely symbolic, but substantial, and the substance of the soul itself. It however does not negate the secular meaning, but historically speaking for the West, the secular idea and the idea of “the secular” structures modern Western thinking and limitations.

It still demonstrates intellectual, moral and spiritual ideas that could bridge our civilizations, rather than defining the world as the separation between civilization and barbarians, or culture and non-cultures. We choose to only understand the term, illuminati confusedly through (a) a diluted secular (demystified) notion, while (b) simultaneously misusing it to mythologize political and financial elites as Illuminati Baal-worshipping occultists.

Zoroastrianism and Suhrawardi share a metaphysical view of light as divine emanation, rooted in Persian heritage, where light and fire actively combat or transcends darkness (falsehood, ignorance, evil, perversion). Weishaupt, however, demystifies it into rational enlightenment, emphasizing intellectual defiance, although acknowledging the Zoroastrian and Christian esoteric roots.

As an active, ethical duty, courage in Zoroastrian martialism is tied to our cosmic battle against evil, requiring bravery in maintaining Truth, or Light; and is embodied in the warrior through martial virtues. Courage, it teaches produces righteous deeds. The path to the perfected human (al-insan al-kamil) for Suhrawardi involves moral fortitude, requiring the aspirant to face mystical challenges, purification, and intuitive leaps beyond rationalism and discursive means. As Allah’s vicegerent, the illuminated embody courage in leadership, justice, and piety.

From this, one might ask whether moral excellence arises from divine fire, rational courage, or intuitive illumination; despite all three being vital to human striving.

Leave a comment