INTRODUCTION

Historical figures involved in French Third Republic (1870–1940) politics were generally opposed to the monarchy, aligning with the prevailing republican and anti-clerical sentiments of the era, though there are nuances1 in this time within esoteric currents.

The Theosophical Society in France, officially established as a section in 1899, attracted and propelled several notable figures who were active in French intellectual and political circles during the Third Republic (1870–1940). Such individuals like Réveillaud, Flammarion, Encausse and others often shared general political and social aims of French secularism and republicanism, which stood in direct often militant opposition to the idea of a restored monarchy and the influence of the Catholic Church in state affairs.

ESOTERIC CURRENTS, PROTESTANTISM AND THE POLITICAL LANDSCAPE OF THE THIRD REPUBLIC

The political landscape of the Third Republic was characterized by a strong divide between monarchists and republicans, with the latter group favoring a secular, representative government. Theosophists in France largely fell into the republican camp, seeing the Republic as more aligned with their ideals of freedom of thought and the separation of Church and State than a traditionalist monarchy tied to the Catholic Church. The Third French Republic saw a notable occult revival, including Theosophy and related esoteric movements. Independent theosophers influenced by Theosophical ideas operated outside the official Theosophical Society (TS, founded by Helena Blavatsky in 1875), and often preferred Western esoteric traditions. The Theos. Soc. held an official presence in France during the Third Republic, but it was limited and faced internal conflicts. Early branches emerged in the 1880s, including the Société Théosophique d’Orient et d’Occident founded in 1883 and led by Marie Sinclair, Countess of Caithness (also known as Lady Caithness or Duchess de Pomar). She was a notable figure in this history, hosting Blavatsky in Paris in 1884 and serving as president of the French branch; and it was Blavatsky who approved its creation during her visit.

There were short-lived groups, which included Isis in 1887, and Hermès lodges. These activities generally were cultural and spiritual, with no documented direct involvement in Third Republic politics of government, legislation, or major political events, being that this was against the Theosophical Society’s constitution. The history of police surveillance of the Theosophical Society also made sure it did not directly get involved.

The Third Republic contained an occult esoteric milieu, which do have structurally political and cultural implications that tie into anti-republican sentiment in contrast to the more republican tones of the Theosophists. Theosophy itself described its role as apolitical, and members involved in politics risked facing expulsion, since if political activity was traced to members of the Theos. Soc., this would endanger it. Martinists sought a divine organic society, critiquing secular republicanism and materialism, which aligned them with monarchist or traditionalist views, but any direct influence on politicians or policies unfortunately remain marginal and undocumented for us researchers.

There were no known or prominent theosophers that shaped Third Republic governance, elections, or policies, but the impact of the Theosophical Movement associated with the Theos. Soc. in France during this period was intellectual and spiritual, contributing to the French Occult Revival (Renouveau occulte) alongside Spiritualism and Hermeticism, rather than political power, as Joscelyn Godwin’s works on early French Theosophy and David Allen Harvey’s Beyond Enlightenment demonstrate.

THREE HISTORICAL FIGURES DURING FRENCH OCCULT REVIVAL INTO BELLE ÉPOQUE ERA

Eugène Réveillaud (1851-1935)

Eugène Réveillaud was an anticlerical, militant protestant politician who served in the French parliament (Chambre des Députés)2. Réveillaud was an ardent advocate for French secularism (laïcité). Being associated with the radical-socialist party, he was originally a freethinker who converted to Protestantism in 1878 and became a fervent evangelist for the faith. He was a Masonic member of the Grand Orient de France, where he advocated for the formation of a liberal and republican Gallican church, but he was not involved in the Theosophical Movement. While Freemasonry in France during the Third Republic sometimes intersected with broader esoteric or spiritualist currents, Réveillaud’s Masonic role was primarily political and joined with republican anti-clerical reforms. As a French journalist, lawyer, Freemason, and politician born in Saint-Coutant, Charente-Maritime into a family of primary school teachers, he was initially raised Catholic, but he rejected it.

He studied at lycée Charlemagne, where he pursued journalism, editing republican newspapers like L’Avenir Républicain in Troyes, also where he earned a law degree and practiced. Converting to evangelical Protestantism in 1878, he became an anti-Catholic campaigner, authoring successful works like La question religieuse et la solution protestante (1878). Réveillaud founded an institution for converted priests in 1884, served in a Waldensian parish in Italy, administered the Société des Traités Religieux, and helped peasants settle in Algeria. Elected deputy for Charente-Inférieure in 1902, he contributed to the 1905 separation of Church and State. He was a prolific protestant of Bible-inspired poetry and historical works, such as Histoire du Canada et des Canadiens.

His interests centered on Protestantism and anti-Catholic activism, and he had no known connections to esoteric or Theosophical movements. However, Réveillaud was a militant republican, actively promoting republican principles through his enpassioned journalism, politics, and advocacy. As a deputy and strongly anticlerical, he participated in debates on Church-State separation3, presenting Protestant Church organization as a model for republican governance, which Protestants accepted as it enabled worship unions. His anti-Catholic campaigns and works emphasized a Protestant solution to religious issues, aligning with secular republican democracy to reduce clerical influence.

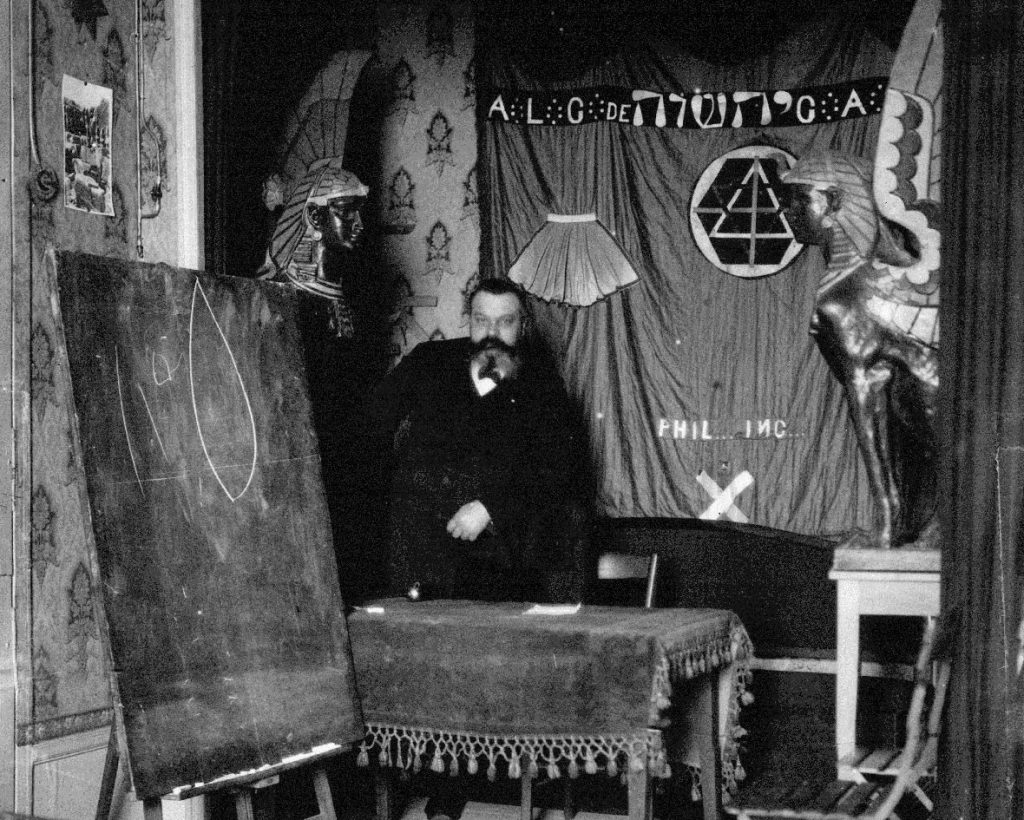

Dr. Gérard Encausse (1868-1916)

Dr. Gérard Encausse, also known as Papus was a prominent occultist, Martinist and once Theosophist, who later diverged into other esoteric movements. Encausse was early on part of an intellectual milieu that generally supported the Republic’s modernizing vision over the traditionalist monarchy, but he was a critic of materialist secularism and secular rationalism. His full name was Gérard Anaclet Vincent Encausse, known as a French physician, hypnotist, and occultist, although born in A Coruña, Spain to a Spanish mother and French chemist father. Raised in Paris, he studied Kabbalah, tarot, magic, and alchemy at the Bibliothèque Nationale. He co-founded Librairie du Merveilleux (1888) and edited L’Initiation journal. After earning an MD from the University of Paris in 1894 with his dissertation on Philosophical Anatomy, he ran a clinic on rue Rodin. Historicallym his legacy is being the founder of the modern Martinist Order in 1891, the Kabbalistic Order of the Rose-Cross in 1888; and also involved in the Gnostic Church, Golden Dawn, and Ordo Templi Orientis. He authored occult books like Le Tarot des Bohémiens (1889). Encausse visited Russia between 1901–1906, advising Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra on occult matters, but died of tuberculosis in 1916 while serving in the French army medical corps during World War I.

Gérard Encausse held an independent connection to the Theosophists, as a physician and leading occultist who joined the French Theosophists shortly after its founding 1884-85, but he resigned soon after, criticizing its Eastern focus. He was briefly involved in the Hermès lodge of 1888, co-founding the Hermes Branch after disputes in the Isis Branch. He edited L’Initiation, blending occultism with Theosophical ideas initially. The Numerical Theosophy of Saint-Martin & Papus (2020), featuring works by Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin (the “Unknown Philosopher”) and Gérard Encausse (Papus) show numerical mysticism influenced by Theosophical concepts. The Hermes Branch was chartered by Theos. Soc. president Henry Steel Olcott, but Encausse was expelled in 1890 amid the disputes. He rejected Theosophy as less “French” and less Christian, preferring the Western esotericism of the Martinists. Hence, viewing Theosophy ambiguously, he distanced Occultism from Theosophy while engaging with related Socialist theories. These kind of figures distanced themselves from Theosophists to focus on Western Occultism, preferring Martinism, or the Kabbalah, even though traditions such as Kabbalah cannot be essentially considered “Western” and “European.” His activities were esoteric and cultural, popularizing occultism among the bourgeoisie. Papus was not involved politically in Third Republic politics, but he is prominent due to his general cultural influence during the occult revival.

His engagement with socialist theories in the July Monarchy era tradition (constitutional monarchy with social elements) reveal the developments of his thinking, since he distanced himself from mainstream republicanism, and rejected anarchism and Marxism. His anti-Semitic writings and conspiracy theories about a Jewish syndicate plot turned him against republican secularism. As an occultist, he focused primarily on individual spiritual development over societal politics, despite involving himself in occult politics among the bourgeoisie. Encausse promoted occultism as an alternative to traditional religion, integrating science and spirituality e.g., involving studies on electric measurements of mediums and their purported otherworldly activity. He distinguished occultism from spiritism, favoring psychic forces over supernatural mysteries, while retaining Christian elements. Distancing himself from mainstream republicanism, he advocated for social reforms within the monarchist system. During the time he served as physician and occult advisor to Tsar Nicholas II, allegedly conjuring the shade of Alexander III, warning them numerously against revolutionaries and Grigori Rasputin.

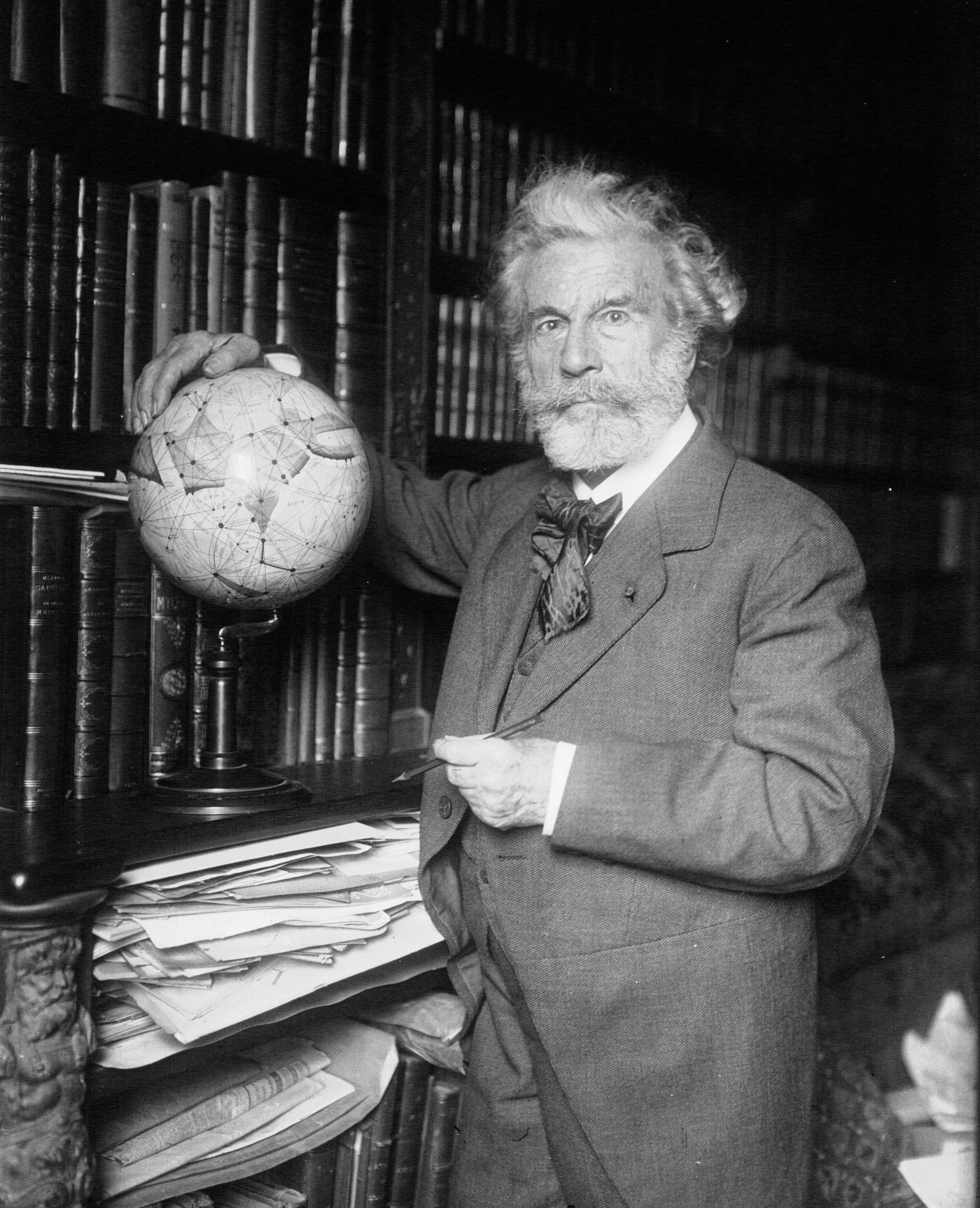

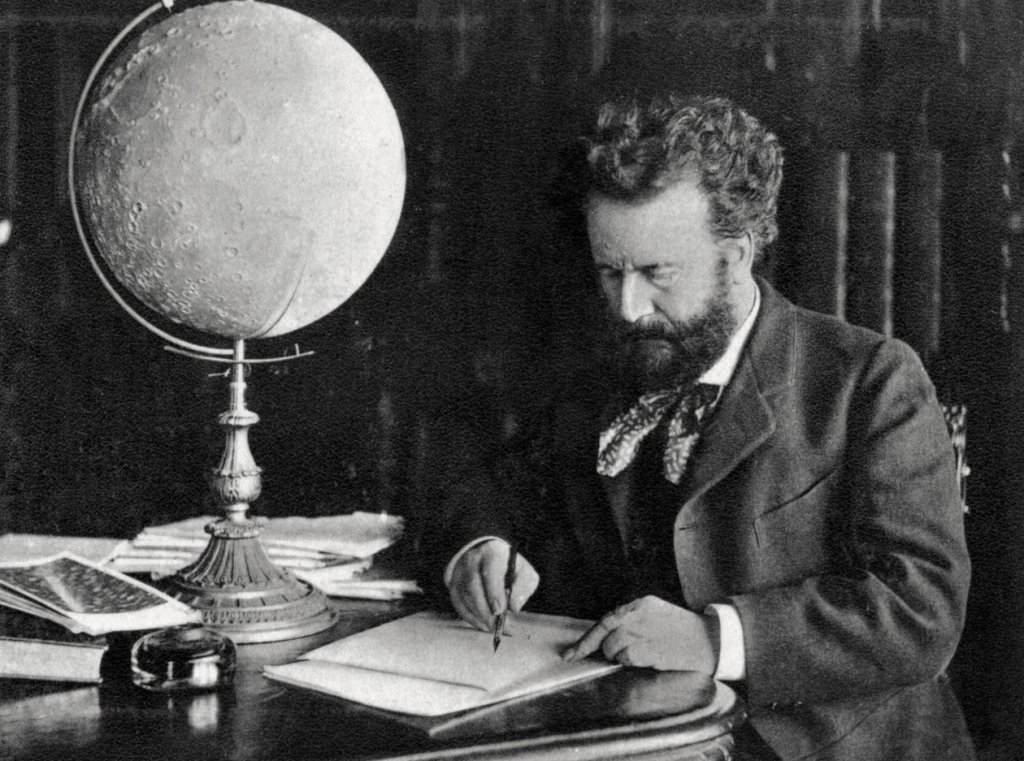

Nicolas Camille Flammarion (1842–1925)

Nicolas Camille Flammarion on the other hand was connected to the Theosaophical Society’s circle. Flammerion is a well-known name in Theosophy, as a renowned astronomer and author who had strong interests in spiritualism. While primarily a scientist, his views aligned with the progressive, secular ideas of the Republic during that period of historical transition in France. He was a French astronomer, author, psychical researcher and romantic republican born in Montigny-le-Roi who joined the Theosophical Society around 1880, serving as an honorary International Vice-President from 1881 to 1888 according to the Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875–1942.

Before this, he worked at the Paris Observatory from 1858, founded the Société astronomique de France, serving as its first president, and published L’Astronomie magazine in 1882. Flammarion was a prolific writer with over 50 titles on astronomy, science fiction, and psychical phenomena, to his name. He maintained an observatory at Juvisy-sur-Orge — influenced by Darwin, Lamarck, and the Spiritism of Allen-Kardec; and took interest in exploring the prospect of extraterrestrial life, soul transmigration, and psychic forces in physics. He had marriages to two astronomers — Sylvie Petiaux-Hugo and Gabrielle Renaudot; and his brother Ernest founded the Groupe Flammarion publishing house. Flammarion received the Prix Jules Janssen in 1897 and was made Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur. As a member of the Theosophical Society, he joined the Theosophical Movement in 1880 alongside scientists like Thomas Edison and William Crookes. He served as a trait-d’union between exact sciences and Theosophy, with ideas corresponding on planetary habitability, spiritual evolution, and cosmic unity as referenced in Helena Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine in 1888.

The views of Flammarion on astronomy, was seeing its study as enlightening the soul and fostering spiritual liberation, clearing the way for Spiritist and Theosophical principles to be recognized. Flammarion supported republican thought, participating in the 1868 Philosophical Congress for Progressive Theism with other civic republicans. As a spiritist and astronomer, he aligned with feminist republican Leon Richer and republicans interested in spiritual matters. He supported utopian reforms tied to the 1848 revolutions, and as a Ligue de l’enseignement member, he promoted secular education under the Third Republic. This effort influenced the Ferry Laws in the early 1880s, promoting public progressive secular education and republican values. These values within the republican framework characteristically promoted anti-clericalism, democratic progress and deistic freethinking, often opposing monarchist Catholicism.

FOOTNOTES

- Helena P. Blavatsky cannot be so easily pegged, because although she expresses republican sentiment, like Dr. Gérard Encausse they are both highly critical of the rise and any subsequent domination of materialist secularism. Encausse took it further, but also like H.P. Blavatsky, a Russian herself, both warned against dangerous emergent revolutionary elements in Russia, and directly against Socialism and Communism. The Communists banned Theosophy until the collapse of the Soviets. For Blavatsky, in her later development, she would say it did not matter whether man lived under a monarchy or republic, but that there needed to take place a deeply ethical, fundamental and transformative change in humanity before social reforms. This idea, so strong in the occult view against animalism and the mechanistic theory of man’s nature and social structure rejects the belief in humanity as individual units and manipulatable creatures moved primarily by their animality. For Encausse, he developed the view that materialist secularism through various revolutionaries were ultimately disastrous, and shifted towards social reforms within monarchism. This explains the often less studied traditionalist/monarchist currents of Occultism, which unfortunately are often used to critique Theosophy and other movements. Recommend reading Helena Blavatsky Critique of the French Revolution of 1789, Material Progress and the Rich ↩︎

- He served as a deputy (1902–1912) and senator (1912–1921) for Charente-Inférieure, affiliated with radical republican groups. ↩︎

- A staunch republican and strongly anticlerical, he was a member of the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party, aligning with the Gauche radicale and Gauche démocratique. He actively participated in Third Republic politics, emphasizing anticlerical reforms. He converted to evangelical Protestantism in 1878, using it to promote republican ideals against Catholicism. Strongly anticlerical, Réveillaud supported the 1905 law separating church and state. His work La question religieuse et la solution protestante (1878) critiques church-state ties, advocating Protestant solutions for secular governance. He founded organizations aiding converted priests and Protestant settlers. As a committed republican and protestant, he opposed monarchical and clerical hierarchies, favoring democratic reforms. ↩︎

REFERENCES

- Theosophist, September 1935.

- Lynn Sharp, Secular Spirituality: Reincarnation and Spiritism in Nineteenth-Century France

- Heed the Prophetic Warnings: Occultism and Conspiracy Theories

- Jan Snoek, Occultist Identity Formations Between Theosophy and Socialism in Fin-de-Siècle France

- Musée protestant, Eugène Réveillaud (1851-1935)

- Musée protestant, “The Law of 1905“

- The Numerical Theosophy of Saint-Martin & Papus

- Gérard Encausse dit Papus: Biographie

- Thelemapedia. “Gerard Encausse.”

- Guggenheim Bilbao, The Merger of Science and Mysticism: The Theories of Camille Flammarion

- US Spiritist Federation. “Camille Flammarion.”

- Psi Encyclopedia. “Camille Flammarion.”

- Theosophy Wiki, “Nicolas Camille Flammarion.”

Leave a comment