MAZZINI’S “DEMOCRATIC WORLD REPUBLIC”: THE COSMOPOLITANISM OF NATIONS

It was Mazzini’s conviction that under the historical circumstances of his time, only the nation-state could allow for genuine democratic participation and the civic education of individuals. To him, the nation was a necessary intermediary step in the progressive association of mankind, the means toward a future international “brotherhood” among all peoples. But the nation could never be an end in itself. Mazzini sincerely believed that cosmopolitan ideals and national sentiment would be complementary, so long as the rise of an aggressive nationalism could be prevented through an adequate “sentimental education.” (Stephano Recchia, Nadia Urbinati: Introduction to Giuseppe Mazzini’s International Thought, 2009, 2)

Revolution is a term denoting destruction of the old world, and the revolving of celestial bodies in its return to its initial position. Republicanism is a radical revolutionary philosophy. Its principal aim is the regeneration and liberation of man and nations, which Mazzini expresses. The premises of the cosmopolitan Mazzini, who dreamed of a democratic world Republic were not the same as Karl Marx, who saw the Nation and the historical duties of its people as based in reality. Karl Marx hated Mazzini, and Friedrich Engels was said to once mock the idea of a “United States of Europe.” However, Karl Marx and the classical Marxists aren’t anti-republican, and must be considered within the republican political tradition. (see “Socialist” or “Social” Republicanism).

Republicanism during the Enlightenment period was a global revolutionary phenomenon throughout France, Spain, China, England, Ireland, and the Americas, etc., carried into the Enlightenment era and the early American Republic from the classical world. This radical philosophy venerates in principle: Virtue, Truth, Justice, Law, Order, Family, UNITY, INTELLIGENCE and Education. It is a philosophy that sees itself as a harbinger of world order, social justice, and human enlightenment.

The spiritual notions in Mazzini’s thought are evident, in that for Mazzini, the nation is something transcendental. It is a voice of the Divine (Deity in Motion, God evolving, “process theology”) in history and nature, manifested through the voice (logos) of the People.

The ‘cosmopolitanism of nations’ serves the People, with the People helping each other in association to liberate the People and incorporate the People. Mazzini’s ideas were adapted into early Fascist Philosophy, which is rooted in the history of Italian thought. Therefore, Mazzini was ironically an influence on both Fascists and Liberal Internationalists. Both the Fascist philosophers and G. Mazzini were influenced by Giambattista Vico. On political alliances, in Mazzini’s period, the main struggle of republican movements was against Imperial Russia, the Latin Church, and the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empire — with the church and conservative forces organized and operating against Freemasons and republican movements.

In the United States, its governing system is a representative democracy — based upon the heritage of ancient Republics and Athenian Democracy and other influences. Americans on either political side have made the terms meaningless, when demonizing them through the actions of those that represent those terms. This linguistic issue contributes to American political pathology.

The particularistic attachment or form of solidarity, be it national, linguistic, religious, territorial, or ethnic, in the republican vision was not anti-liberal, anti-nationalist, anti-classical, nor anti-cosmopolitan. The change may be attributed to the progressive intellectual tradition, which was being touted around the New Deal period as a new liberalism for a new century, to face the challenges of an American society no longer reliant on the agrarian economy of its founding era. Damon Linker argued, but now liberals have undergone a complete reversal, treating something once considered a given as something that must be extricated root and branch (Liberals keep denigrating the new nationalism as racist. This is nonsense). Hence, Liberals have sought to find a way to get back the perception, that radicalism and resistance do not exclude them as patriots and veterans who love their country, even when criticizing it and holding it accountable to its principles.

“INTRODUCTION TO GIUSEPPE MAZZINI’S INTERNATIONAL THOUGHT”

By Stefano Recchia and Nadia Urbinati

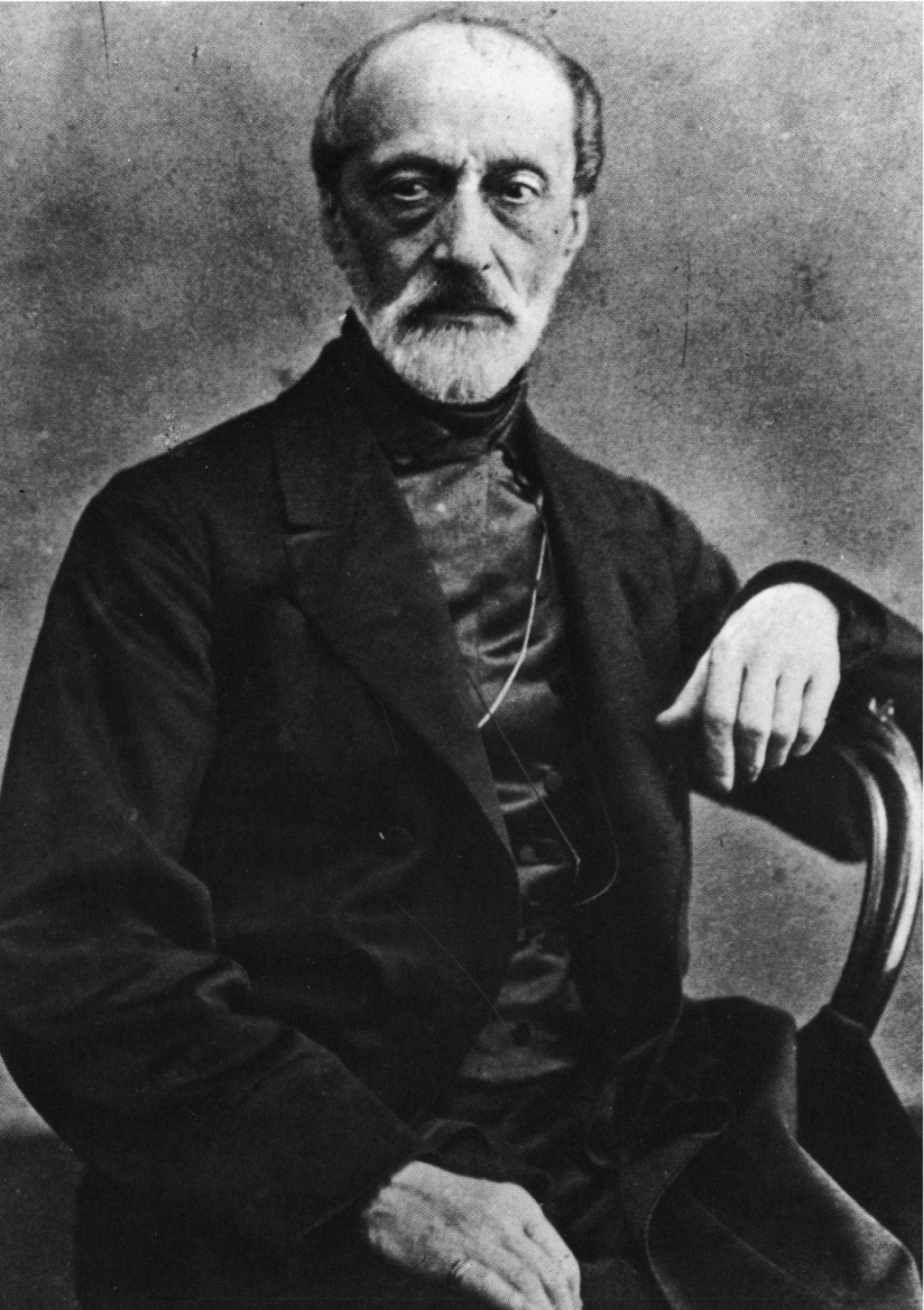

“Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–72) is today largely remembered as the chief inspirer and leading political agitator of the Italian Risorgimento. Yet Mazzini was not merely an Italian patriot, and his influence reached far beyond his native country and his century. In his time, he ranked among the leading European intellectual figures, competing for public attention with Mikhail Bakunin and Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville. According to his friend Alexander Herzen, the Russian political activist and writer, Mazzini was the “shining star” of the democratic revolutions of 1848. In those days Mazzini’s reputation soared so high that even the revolution’s ensuing defeat left most of his European followers with a virtually unshakeable belief in the eventual triumph of their cause.

Mazzini was an original, if not very systematic, political thinker. He put forward principled arguments in support of various progressive causes, from universal suffrage and social justice to women’s enfranchisement. Perhaps most fundamentally, he argued for a reshaping of the European political order on the basis of two seminal principles: democracy and national self-determination. these claims were extremely radical in his time, when most of continental Europe was still under the rule of hereditary kingships and multinational empires such as the Habsburgs and the ottomans. Mazzini worked primarily on people’s minds and opinions, in the belief that radical political change first requires cultural and ideological transformations on which to take root. He was one of the first political agitators and public intellectuals in the contemporary sense of the term: not a solitary thinker or soldier but rather a political leader who sought popular support and participation. Mazzini’s ideas had an extraordinary appeal for generations of progressive nationalists and revolutionary leaders from his day until well into the twentieth century: his life and writings inspired several patriotic and anticolonial movements in Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East, as well as the early Zionists, Gandhi, Nehru, and Sun Yat Sen.

It was Mazzini’s conviction that under the historical circumstances of his time, only the nation state could allow for genuine democratic participation and the civic education of individuals. To him, the nation was a necessary intermediary step in the progressive association of mankind, the means toward a future international “brotherhood” among all peoples. But the nation could never be an end in itself. Mazzini sincerely believed that cosmopolitan ideals and national sentiment would be complementary, so long as the rise of an aggressive nationalism could be prevented through an adequate “sentimental education.” As we will argue in more detail below, he was thus a republican patriot much more than a nationalist. The nation itself had for him a primarily political character as a democratic association of equals under a written constitution. Like a few other visionaries of his time, Mazzini even thought that Europe’s nations might one day be able to join together and establish a “united States of Europe.” His more immediate hope was that by his activism, his writings, and his example, he would be able to promote what today we might call a genuine cosmopolitanism of nations—that is, the belief that universal principles of human freedom, equality, and emancipation would best be realized in the context of independent and democratically governed nation-states.

Mazzini clearly believed that the spread of democracy and national self-determination would be a powerful force for peace in the long run, although the transition might often be violent. Where oppressive regimes and foreign occupation made any peaceful political contestation virtually impossible, violent insurrection would be legitimate and indeed desirable. Democratic revolutions would be justified under extreme political circumstances. However, he expected that once established, democratic nations would be likely to adopt a peace-seeking attitude in their foreign relations. democracies would become each others’ natural allies; they would cooperate for their mutual benefit and, if needed, jointly defend their freedom and independence against the remaining, hostile despotic regimes. over time, democracies would also set up various international agreements and formal associations among themselves, so that their cooperation would come to rest on solid institutional foundations. In this sense, Mazzini clearly anticipated that constitutional republics would establish and gradually consolidate a separate democratic peace” among each other. He did so much more explicitly than Immanuel Kant (…).

For these reasons, Mazzini deserves to be seen as the leading pioneer of the more activist and progressive “Wilsonian” branch of liberal internationalism. There is indeed some evidence that President Woodrow Wilson, who later elevated liberal internationalism into an explicit foreign policy doctrine, was quite influenced by Mazzini’s political writings. On his way to attend the 1919 peace conference in Paris, Wilson visited Genoa and paid tribute in front of Mazzini’s monument. The American President explicitly claimed on that occasion that he had closely studied Mazzini’s writings and “derived guidance from the principles which Mazzini so eloquently expressed.” Wilson further added that with the end of the First World War he hoped to contribute to “the realization of the ideals to which his [Mazzini’s] life and thought were devoted.”

RECOMMENDED READING: A COSMOPOLITANISM OF NATIONS: GIUSEPPE MAZZINI’S WRITINGS ON DEMOCRACY, NATION BUILDING, AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Leave a comment