INTRODUCTION: ECLECTIC MASONIC PHILOSOPHER IN CONFLICT

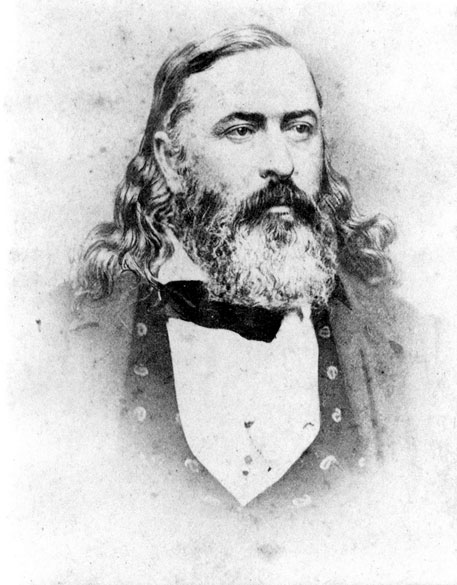

Albert Pike’s editorial career exhibits a philosopher highly in conflict with himself, and I hope his inner conflicts alongside his philosophical legacy may provide us the chance for reflection about similar men of our day. People fixate on Albert Pike’s pro-slavery stance (and often exaggerate or distort it) for a combination of historical, ideological, and cultural reasons. Pike was a prominent Confederate general, a Scottish-Rite Freemason, and author who supported slavery and defended it both before and during the American Civil War. He resigned his commission in July 1862 (effective November 1862) amid controversies over his command of Native American troops in the Indian Territory, including accusations of misconduct and atrocities at the Battle of Pea Ridge. After the war, he received a presidential pardon in 1865 and lived out his remaining decades primarily as a lawyer, poet, and prominent Freemason in Washington, D.C., where he died on April 2, 1891, at age 81.

The long arc of Pike’s life and achievements are ignored in the public narrative, limiting his history into the 1860s. Due to the fact that Pike is the most famous Scottish Rite Mason in history, critics who already distrust Freemasonry (e.g., evangelical Protestants, John Birch-style conspiracists, certain New Left anti-elitists) find it convenient to tie the entire fraternity to slavery and white supremacy through him; and to maintain this narrative as much as possible.

The claims against him are complex, because of a mixture of past hoax letters blended with neo-Confederate quotes in the modern digital era that cleverly paraphrase and provide fake sources. This is seen more frequently e.g., with founding fathers and lately Benjamin Franklin’s fabricated views against Jews. These fabrications seek to portray the U.S. founders as privy to the “Great Noticing.” There are a good number of fabricated quotes supposedly written by Pike. We know several to be lies, because Pike’s verified 1880s letters (e.g., to Masonic brethren) discuss philosophy and rituals, not Confederate narratives; and he critiqued the Civil war’s “follies” in private notes, supporting Reconstruction-era Native claims against the South. This indicated some return to his original positions.

Early WHIG Anti-Slavery Sentiments AND EDITORIAL BEGINNINGS (1830s)

Pike often reversed his position on slavery, revealing this conflict. His post-war writings avoided Confederate apologetics to focus on national reconciliation, which became very noticeable after the 1860s. Lause’s A Secret History of the Civil War (2011) notes, Pike also shifted in the 1880s toward anti-sectarianism. Lost Cause proponents tried to portray Pike as a proponent of the Lost Cause movement to get more Confederate statues erected, despite evidence of Pike’s post-1862 disengagement.

In his younger years in 1837, he was 28 and had already denounced Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal policy, calling slavery a moral evil in print. In the 1850s he flip-flopped several times, defending slavery when running for office in a pro-slavery district, then privately called it “a curse” in letters. Pike’s early anti-slavery stance in 1837 reflected Northern Whig moralism, and is addressed in the Arkansas Advocate, Aug 18371 when Pike stated, that “Slavery is a moral and political evil.”

His early anti-slavery and pro-Native sentiments appear influenced by his abolitionist-leaning Massachusetts roots and journalistic role. However, as he integrated into Southern politics and society, his views shift toward a pragmatic defense of slavery, often described as a “necessary evil,” while maintaining advocacy for Native rights.

This is known, because when Pike first arrived in Arkansas between 1833–1835, he edited the Little Rock Arkansas Advocate as a Whig paper. In that period he occasionally published mild anti-slavery sentiments, e.g., reprinting Northern abolitionist pieces or criticizing the “peculiar institution” in abstract moral terms. This was typical of many border-state Whigs who disliked slavery in principle but did not advocate immediate abolition.

Pro-Slavery Advocacy and Secession (1850s–1860s)

Pike eventually changed position, writing pro-slavery pieces in the same Arkansas Advocate in the mid-1850s, defending secession in 1861. He became a leading voice for the pro-slavery Democratic faction in Arkansas; thus, in this period, Pike became an ardent secessionist. In the same year in 1861 he published poetry and articles celebrating Arkansas’s secession in the True Democrat, urging the South to fight for the right to maintain slavery. After Lincoln’s election, directly opposite of the position Mazzini took in hoping Lincoln would abolish slavery, is when Pike became one of Arkansas’s most outspoken secessionists. Pike helped draft Arkansas’s secession ordinance and personally recruited. After secession he then accepted a commission as a Confederate brigadier general and commanded the Department of Indian Territory, where he negotiated treaties with Native American tribes that explicitly protected the institution of slavery within their nations. Just because he favored particular Native American tribes does not negate his racism against Black people.

This was undoubtedly the most indefensible phase of his highly conflicted life. This shift could be explained by a mix of political ambition, seeing that the Whigs were dying out in the Deep South, financial interests due to marrying into a slave-owning family, and genuine ideological hardening on race and states’ rights.

These pro-slavery editorials are in the Arkansas Advocate 1854–18602. After the war, Pike never defended slavery again and eventually supported Black Masonic lodges (Prince Hall recognition) when most white Southern Masons refused3. The claim, that Pike was influential on the KKK is highly disputed by a number of scholars4.

INTELLECTUAL PEDIGREE AS POLYMATH, LINGUIST, AND SCHOLAR AND NATIVE AMERICAN ADVOCACY

The controversial history of Pike speaks to less of the usual villainous caricature, whether portrayed as hagiographic Masonic saint, Confederate traitor, or “Satanist.” Pike’s far more substantial (and, to many, admirable) contributions as a scholar, linguist, and Masonic reformer too often get sidelined or dismissed as irrelevant once they latch onto his positions on “slavery.” There is also within American culture itself, simply no care for the knowledge Pike was interested in.

There are an ample number of historians, Masonic scholars, and contemporaries who knew his work intimately. He cannot be defined merely as an admirer or plagiarist of Eliphas Levi, given the larger depth of his interests and writing. Largely self-educated, Pike taught himself at least a dozen languages well enough to read primary philosophical and esoteric texts in the original Sanskrit, Persian, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Old French, German, and others5.

Before Blavatsky, Olcott, or the Golden Dawn, Pike was introducing large numbers of educated Americans to genuine, even if distinct, readings of Vedanta, Zoroastrianism, Kabbalah, Neoplatonism, and Gnosticism. Scholars such as Joscelyn Godwin and John Patrick Deveney argued that Morals and Dogma operated as an underground “university curriculum”6 in esoteric thought for generations of American intellectuals who had no other access to those traditions.

His private library in Little Rock eventually exceeded 10,000 volumes7. He translated and annotated large portions of the Rig Veda and Zoroastrian Avesta decades before most English versions existed, hence before Müller or Darmesteter8. Contemporaries described his linguistic ability as “prodigious,” and his personal correspondence shows he could switch between English, French, Spanish, Latin, and occasionally Cherokee in the same letter.

Anti-masons often cheapen the facts surrounding his time with advocacy for Native American Rights between the 1830s–1850s, as a young lawyer and newspaper editor in Arkansas. Within this time period, Pike repeatedly defended Cherokee and Choctaw land rights and sovereignty in print, at a time when Indian removal was popular in the South. These defenses of Cherokee sovereignty and land claims in print and court are revealed in Brown’s Life of Albert Pike (pp. 121–132), Allsopp’s work (Albert Pike, pp. 92–104), and Carter’s The Territory of Arkansas (1949, pp. 201–205). He represented Native tribes on major cases against the U.S. government (U.S. Supreme Court records, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia aftermath cases, 1838–1842; Brown, pp. 128–130), and spoke and wrote Cherokee fluently (Brown, p. 126; personal letters in Pike Papers, University of Arkansas).

While his later Confederate service complicates this picture, his early record on Native issues was far more progressive than most white Southerners of his era. This was likely connected to his views of the Reconstruction era as representing the ideals of a tyrannical order.

In his lifetime, he did manage to achieve some accomplishment and recognition as a poet. Pike’s poetry (especially hymns like “The Day Spring” and longer works like “To the Mocking-Bird”) was widely anthologized in the nineteenth-century and praised by figures such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Allsopp, Albert Pike, pp. 145–162, Brown, Life of Albert Pike, pp. 89–95). Modern taste finds it overwrought, but in the mid-Victorian period it was considered serious literary work.

All primary biographies and modern scholarly works (such as de Hoyos, Tresner and Godwin) agree that Pike’s views on slavery evolved significantly over his life and were far more complex than the one-dimensional caricature that dominates common discourse.

Seen as a brilliant, eccentric, nineteenth-century American polymath during his time, Pike poured an astonishing amount of learning into the Scottish Rite, which would otherwise have remained a social club without his work. It is chiefly because of this, that his fellows sought to erect his statue. Pike’s history with pro-Confederate sympathies and racial paternalism do not negate the scale of his intellectual achievement within the world of nineteenth-century Freemasonry and esoteric studies. Pike almost single-handedly transformed the Scottish Rite from a loose collection of often incoherent degrees into a philosophically coherent system. Morals and Dogma (1871) is still the single most ambitious attempt to synthesize comparative religion, philosophy, symbolism, and ethics within Freemasonry. Modern scholars like Arturo de Hoyos, who annotated the definitive modern edition, credit Pike with giving the Rite an intellectual depth it previously lacked in America. Pike didn’t just edit rituals but rewrote most of the 4°–33° between 1855 and 1880, infusing them with Kabbalistic, Hermetic, and Vedantic elements in a way that was unprecedented in Anglo-American Freemasonry9.

POST-WAR WRITINGS ON ANTEBELLUM SOUTHERN RECONSTRUCTION ERA VERSUS MODERN FABRICATIONS

Now, we must contend with the belief that Albert Pike believed in the superiority of the pre-war Southern order. It is true, that Pike laments the end of the old Southern system in his public life, in speeches and in private correspondences wherein he portrays the South as fighting for principles of liberty and State sovereignty, while describing Reconstruction as tyrannical, implicitly justifying the pre-war social order.

It can be thus summed up, that Pike’s post-war writings, speeches, and private letters repeatedly and consistently show that he regarded the antebellum Southern social and political order as superior to what replaced it after 1865. He never renounced the core principles for which the Confederacy fought (state sovereignty, limited central government, and the social hierarchy of the slave South), and he viewed Reconstruction as an illegitimate, tyrannical imposition by the North. Carl Moneyhon (The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas, 1994) describes Pike’s role as one of the leading journalistic voices of the anti-Reconstruction forces in the state.

In this sense for him, the antebellum Southern system was the truest expression of liberty and good order. Like most of these historical individuals, their ideals became absorbed into the larger framework of the United States.

Finding statements on his racism are mixed heavily with unsourced online neo-Confederate embellishments, which takes sifting through for accuracy. Nevertheless, it is true, that Pike expressed sympathies with Southern resistance and “redemption” narratives, which were efforts to restore White democratic rule. Pike’s real Reconstruction views were shaped by his Whig background and Confederate service, which he saw as an overreach, but shifted focus to legal and Masonic matters post-1874 to avoid controversy.

In one of these claims, it is stated that in context to the pre-war South and defense of its principles in an 1868 letter to his brother Walter Albert Pike stated that, “I am still the same earnest lover of personal liberty, of State rights, and of the Constitution as it was…The South fought for the perpetuation of those principles.” (Walter L. Pike papers, University of Arkansas). This is attached to another claim about a 1870 poem titled “Dixie” (revised version), where he portrays the Confederate soldier as having fought for “the rights our fathers gave us” and “the land of constitutional liberty,” equating the Old South with true freedom.

This often appears alongside the definitively false 1887 Maury letter as part of a single, misleading narrative designed to provide fabricated evidence for a Lost Cause version of history. While Pike genuinely held strong beliefs in state sovereignty and personal liberty he defined in ways that supported racial hierarchy and the South’s cause, the specific quote and citation to the “Walter L. Pike papers, University of Arkansas” is not confirmed by reliable historical sources.

In Memphis Daily Appeal editorials (1867–1868) articles written under pseudonyms some have attributed to Pike, repeatedly called Radical Reconstruction “a military despotism,” “Africanization of the South,” and “the overthrow of Anglo-Saxon civilization.”

Another one supposedly written April 1868 reads “The bayonet rules the South…the Constitution is dead, and the negro and the carpet-bagger reign in its stead.” Supposedly, there was a Letter to the Arkansas Gazette, 1874 during the Brooks-Baxter War, in which Pike under his pseudonym praised the conservative “Redeemer” faction and the Reconstruction government as “a foul and loathsome tyranny.”

The quote exaggerates a real April 20, 1874 Gazette letter where Pike calls the regime a “despotic faction.” The Redeemers frequently employed this kind of language in their rhetoric, and are consistent with Pike’s views at the time.

The Brooks-Baxter War (1874 Arkansas political crisis) was a disputed Arkansas gubernatorial conflict between Republican Joseph Brooks and incumbent Elisha Baxter (a Redeemer ally), resolved by federal intervention favoring Baxter. Pike, from D.C., actively intervened through letters and telegrams to President Grant, urging recognition of Baxter to end Republican “corruption.” Brown’s biography (pp. 420–425) reproduces Pike’s Gazette letters verbatim, noting support for Baxter as “the conservative choice” against “Reconstruction excesses.” Pike’s involvement is well-documented, because he lobbied Grant successfully, helping end Arkansas Reconstruction early (Constitution of 1874).

This is an example of mixing historical fact and sources from reputable book material in another claim from an alleged 1885 speech reported in the New Orleans Picayune at the unveiling of the Lee Monument in New Orleans. Pike is made to say that, “We fought for the rights of the States… for the principles of 1776 and of the Constitution of 1789…We were right, and history will yet vindicate us.”

I have not been able to verify this speech. The war was framed in this eulogy, as is done often in Lost Cause mythology, as a noble struggle for “the rights of the States” against centralized tyranny, invoking the American Revolution (the “principles of 1776”) and the U.S. Constitution (1789). The South’s defeat did not disprove its cause’s righteousness in this view, which predicts future vindication of the Confederacy. Romanticizations about the Confederacy seek to downplay the centrality of the slave system to its position and plans of expansionism.

This is a clever tactic in fabricating and misrepresenting sources. Here is a letter to former Confederate general D. H. Maury in 1887, in which supposedly Pike argued “The old order was the best the world ever saw for the negro and the white man alike…The South was happier, more prosperous, and more truly free before the war than it has ever been since.”

An individual can cite Walter L. Brown, Life of Albert Pike, 1997, p. 448 as the source of this letter. Walter L. Brown’s biography is a legitimate, authoritative historical source on Pike, which has been used here, but the mention of this specific quote in his work occurs in the context of Brown debunking the letter as a fraud or discussing the prevalence of these types of claims. Historians and archivists have consistently confirmed this letter to D.H. Maury does not exist.

Pike provided no public retraction or regret for the fall of the antebellum Southern order, which bolsters the arguments for certain people, even despite its fabricated status. Unlike some former Confederates who softened their views late in life, Pike did grow bitter, and perhaps the more he lived in poverty. Much later, Pike like Robert E. Lee urged reconciliation, but no regret for the cause of the Confederacy.

Pike avoided public Lost Cause advocacy to safeguard his Masonic role, emphasizing “non-sectarian” unity; and no direct 1880s correspondence with core Lost Cause bodies like the Southern Historical Society (SHSP) or United Confederate Veterans (founded 1889) exist on record.

In the 1880s10 he was in private defending the righteousness of the Southern cause in exactly the same terms he had used in 1861 in his pamphlet titled “State or Province, Bond or Free?” This hardening is said to be evidences by his increasing reclusiveness and resentment, but his reclusiveness involved him retreating to Masonic duties and philosophical output. Albert Pike and his wife Mary Ann Hamilton had been effectively separated (though not legally divorced) since the late 1850s. By the 1880s the marriage was long over in practice; and they lived apart. The strain was no longer acute, since his Mary Ann remained in Little Rock with some of the surviving children, while Pike spent increasing amounts of time in Washington, D.C., working on Scottish Rite matters. Hence in the 1880s, after ending his law partnership with Luther Johnson and having long been separated from his wife (with six of their ten children having died) Pike lived modestly in D.C., relying on Masonic stipends despite a “substantial private library.”

Brown’s biography (pp. 450–460) describes him as “reclusive and embittered,” with letters lamenting “war follies” while blaming Northern “fanaticism” more than Southern errors.

CIVIL WAR CAMPAIGN, MILITARY CAREER AND POST-RECONSTRUCTION ERA

Multiple biographers such as Walter L. Brown (A Life of Albert Pike, pp. 421–423) and Fred Allsopp (Albert Pike: A Biography, pp. 278–282) emphasize that Pike died relatively poor despite many opportunities for graft as a lawyer, judge, and newspaper owner in a frontier state notorious for corruption. This was because, he turned down lucrative railroad and banking retainers that conflicted with his principles11.

Though his military career is usually mocked due to the Pea Ridge disaster, Pike’s brigade of Native American troops was one of the very few Confederate units that did not commit documented atrocities against Union prisoners or civilians. There are no documented atrocities by his Indian brigade, unlike many others12. After the war he refused to take the Ironclad Oath13 and went into brief exile in Canada rather than perjure himself. He spent his last decades focused almost entirely on Masonic scholarship and helping rebuild the Scottish Rite in the South, not on Lost Cause mythology.

Pike was indicted for treason in 1865, though the charges were later dropped, then he was briefly imprisoned in 1865 and had much of his property confiscated or destroyed during the war. President Andrew Johnson pardoned him in 1865, partly through Masonic connections, but Pike remained bitterly opposed to Radical (Congressional) Reconstruction. For this, he vehemently rejected the Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which placed the South under military rule, required Black male suffrage, and demanded new state constitutions. This was further demonstrated in his views towards the Freedmen’s Bureau, Union League, and Black militias as tools of Northern oppression, fearing “Negro domination” in Arkansas politics.

Pike struggled with Reconstruction (1865–1877) tremendously. These struggles are personal, political and ideological. It is argued, that his contributions to the Reconstruction era were largely negative or obstructive from the perspective of federal Reconstruction policy. This animosity brings us to the conclusion, that it was fueled by personal legal and financial ruin.

In editorials in the Memphis Daily Appeal between 1867–1868, where he briefly lived in exile to avoid arrest, he denounced Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner and the Republican Party in racist terms. When Arkansas was readmitted in 1868 under a Radical constitution, Pike refused to take the “Ironclad Oath” of loyalty, which barred most ex-Confederates from voting or holding office. This left him effectively disenfranchised and politically powerless during much of Reconstruction.

From 1868 onward, after returning to Arkansas, Pike wrote pseudonymous editorials attacking Reconstruction governments. This is when he frequently used pen names such as “A Conservative,” “An Old Democrat,” “Casca,” or simply initials. This unfortunately helped shape Conservative White rhetoric that portrayed Reconstruction as corrupt rule.

In 1867–1868, while living in Memphis, Pike was alleged by some post-war investigators, most notably the 1871–1872 Congressional Joint Select Committee on the Condition of the South, to have been involved in revising or authoring higher-degree rituals for the early Ku Klux Klan.

Walter L. Brown and Duncan find the evidence for this circumstantial and weak; while anti-Masonic writers treat it as fact. This is due to the fact, that there are no primary sources for this claim, but not enough to dispute the fact, that regardless of direct authorship, Pike’s 1867–1868 Memphis period coincides with the Klan’s rapid growth in Tennessee; and his editorials reflect the Klan’s goals of White supremacy and resistance to federal authority. Pike however publicly denied membership, and due to his strong public views during the Reconstruction era, there is initially no good reason to believe he would hide his membership. However, this follows a pattern during the early 1870s, when Pike was involved in the Arkansas Democrats’ Redemption Movement. By the early 1870s, Pike quietly supported Arkansas Democrats (the “Redeemers”) who sought to use violence and intimidation to overthrow the Republican state government. During the Brooks-Baxter War (1874), a violent dispute between two Republican factions in Arkansas; and Pike backed the conservative Baxter faction, which ultimately helped end Radical rule in the state.

Pike’s post-Reconstruction writings and lectures still may have contributed to the popularization of Lost Cause elements and mythology, which portrays the Confederacy as noble and Reconstruction as tyrannical. In connection to my thesis throughout these investigative papers on Pike, I gradually demonstrate how Pike’s Confederate narrative became absorbed by and integrated into the Union, with his statue standing as a monument to his philosophical scholarships, and not his Confederate war days.

ANTI-CATHOLIC AND ANTI-MASONIC INFAMOUS “TAXIL HOAX” AND OTHER FABRICATIONS

Lets turn to Pike’s actual vision for the Republic. Was it a “vision of the South,” a vision of a hierarchical World Empire, which represents God’s reign on earth? This is the public narrative. What are the facts.

We are told, that roughly in the years 1859 and 1871, Mazzini and Pike maintained a correspondence, wherein Mazzini appointed Pike as the organizational chief of global “Universal Masonry” in 1870. This alleged “Mazzini and Pike correspondence” comes almost entirely from a single source; that of the French anti-Masonic author Léo Taxil (real name Marie Joseph Gabriel Antoine Jogand-Pagès) and, later expanded upon by the British conspiracy writer William Guy Carr.

It is true, that Mazzini remained consistent in his anti-slavery stance throughout his life, but also went through several developments, e.g., his early positions on Socialism changed to harsh critic, which H.P. Blavatsky’s development of political opinion reflected. Mazzini sought a world of free democratic nations, that would eventually federate. Mazzini and Pike’s political visions for the structure of a world order looks somewhat similar, since both wanted the end of monarchies and the establishment of republics everywhere, but there are differences to explore. Conspiracists utilize this in their tactics to embellish connections.

There are two main hoaxes, which cleverly used phrasing from Pike’s works to falsely portray a coincidence of ideas, even after proven to be hoaxes. There’s the hoax of the 1880s letter to the Supreme Council of Charleston, which is unverifiable.

In this hoax it is alleged that Pike immediately used the authority Mazzini had given him to transform the Scottish Rite into something much closer to an esoteric, quasi-religious order whose ultimate political aim was not democratic nationalism, but a hierarchical world theocracy.

Originating in 1894, Léo Taxil and a collaborator named “Dr Bataille” (pseudonym of Charles Hacks) fabricated a story claiming that Albert Pike, Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite Southern Jurisdiction (1859–1891), had been appointed by Giuseppe Mazzini as the head of a secret “Palladian Rite” that supposedly directed world Freemasonry from Charleston, South Carolina. According to this hoax letter to the Supreme Council of Charleston, 1880s, Pike viewed the people in a paternalistic way, as children to protect and nurture, referring to the true name of the government of the future to be “the Holy Empire, the reign of God on earth through His priests.”

Despite the fact, Pike never said this, the hoax letter uses phrases Pike used before such as “Holy Empire,” but Pike referred to a metaphorical description of personal spiritual victory, not a literal future political government or theocracy “through His (Masonic) priests.” Then again, knowing that people have not read his work Morals and Dogma and Indo-Aryans, they could not see that the hoax, which claims Pike wants to bring about a new priestly-caste system, contradicts his positions in Morals and Dogma.

The actual original passage the hoax borrowed the phrasing from reads thus:

“Freemasonry is the subjugation of the Human that is in man by the Divine; the Conquest of the Appetites and Passions by the Moral Sense and the Reason; a continual effort, struggle, and warfare of the Spiritual against the Material and Sensual. That victory, when it has been achieved and secured, and the conqueror may rest upon his shield and wear the well-earned laurels, is the true Holy Empire.” (Morals and Dogma, 1871, p. 852; in the 32nd Degree, “Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret”)

Pike repeatedly points the candidate, or aspirant to the belief in the inner triumph of the soul over base instincts, reiterating that through Masonic brotherhood uniting humanity in peace. This strengthens the refutation of lies about Pike’s religious beliefs as dealt with in Albert Pike Ponders on Lucifer in Morals and Dogma: Tells Us to Seek the Light of Knowledge.

These hoaxes have a pattern of cherry-picking and twisting Pike’s real elitism and symbolism to fit a conspiratorial narrative of Masonic world domination. Pike was paternalistic toward the “multitude” similarly to Mazzini, and he used the phrase “Holy Empire” evocatively, but never in the context of a future priest-ruled government. Pike’s actual vision as in his 1871 correspondence with Giuseppe Mazzini or Indo-Aryan Deities in the 1880s criticized the caste-system, and was for a universal republic guided by enlightened non-sectarian Masons, not a priestly theocracy. He criticized clerical power (e.g., in Morals and Dogma, railing against “priestcraft”), as was the customary attitude of the revolutionary republican, and saw Masonry as a counter to dogmatic religion.

The facts begin to contradict the hoaxes upon examination. The Supreme Council (Southern Jurisdiction) was headquartered in Charleston until 1870, when it relocated to Washington, D.C. (House of the Temple). Pike served as Sovereign Grand Commander from 1859 until his death in 1891, and while he did write extensively to the Council (e.g., circulars and reports in the 1870s–1880s), none contain this language. Official minutes and correspondence from that era, preserved in the House of the Temple archives, discuss ritual revisions, organizational matters, and philosophical lectures, not futuristic theocratic governments.

In the second, most famous hoax, it is a notorious nineteenth-century literary prank that also involved libel against the Theosophical Movement, known as the Taxil hoax14. The letter first appeared in Le Diable au XIXe Siècle (or The Devil in the 19th Century, 1892–1894), a multi-volume work pseudonymously authored by a “Dr. Bataille.” As addressed Léo Taxil’s real name was Gabriel Jogand-Pagès, a French anti-clerical writer turned hoaxer. Taxil fabricated tales of Satanic Freemasonry, including Pike as a “Luciferian pontiff” plotting global chaos. The letter is in Volume II, Chapter 25 (“Plan of the Secret Chiefs”), pp. 594–606, dated August 15, 1871, and outlines anti-clerical strategies through engineered wars.

The core text was a short anti-Catholic policy memo. Later fabricators, e.g., Edith Starr Miller in Occult Theocrasy (1933) and Cardinal Caro y Rodríguez in The Mystery of Freemasonry Unveiled (1928) expanded it. William Guy Carr in the 1950s added the “three world wars” prophecy, inserting terms like Nazism, Zionism, and the State of Israel (did not exist in 1871) claiming it was displayed in the British Museum, which it never was.

In 1897, Taxil publicly confessed at a press conference that his entire twelve-year anti-Masonic-Satanic series was a hoax to mock both gullible Freemasons and Catholics, who lapped up his tales. Taxil profited immensely and laughed at the fallout, saying it exposed credulity on all sides.

Despite this, Pike was the only former Confederate general with a statue in Washington, D.C., and this made him a symbolic target in the movement to get rid of Confederate statues. If one is honest in their research on Pike, then it is not the most reputable and true position to simplify his legacy. While, in our time, the attempt is to freeze him in the context of his views pre-1960s, there existed a pattern of apocryphal stories invented in the late nineteenth to twentieth centuries to support “Lost Cause” propaganda, portraying Confederate figures as unrepentant martyrs. Unsubstantiated deathbed tales were attached to Albert Pike, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and other leaders to evoke Southern sympathy amidst Reconstruction and Jim Crow-era memorialization. Pike, despite his brief Confederate role, was not a central Lost Cause icon; and moreover, his Masonic focus made him an awkward fit for fabrications, limiting clever embellishments of Pike’s words to past dates.

They are still effective as a means for propaganda, and to provide legitimacy in the other case of co-opting Pike to support “Lost Cause”/MAGA adjacent parallels. Keep in mind these tactics as I’ve shown are also used against Theosophy, and there are more patterns and examples I will provide, which involve quoting individuals in random papers related to their subjects, even though the quote, passage or individual is nowhere mentioned in the provided quote.

ADDITIONAL CASES OF FABRICATIONS FROM FRINGE TWENTIETH-CENTURY NEO-CONFEDERATE TEXTS

Here are a couple more cases involving more modern fabrications about Pike, utilizing rhetorical parallels.

It was reported in his deathbed statement, 2 April 1891 according to his physician and close friend Dr. J. A. Henry (who was present), that Pike’s final coherent words included, “Tell my brethren that I die firm in the faith that the South was right.” This was supposedly recorded by Dr. Henry and published in the Arkansas Gazette, 4 April 1891, then later in the official Scottish Rite obituary.

This deathbed account provided is a case of myth making, and first surfaced in fringe twentieth-century texts (e.g., pro-Confederate pamphlets) without primary sourcing, then circulated online in conspiracy forums often without scrutiny. In the works of Fred W. Allsopp’s Albert Pike: A Biography (1928) and Mark A. Lause’s A Secret History of the Civil War (2011), Pike’s final days are documented as delirious from illness, with no coherent political statements recorded. His last verified words, according to witnesses were mundane or Masonic in tone, not Confederate.

The quote aligns with Pike’s known pre-war secessionist views (e.g., his 1861 editorials), making it plausible only on the surface.

There are no digitized historical newspapers with a trace of this article or quote. While Pike’s death on April 2 was reported in the Gazette around that date, it focused on his Masonic achievements, legal career, and peaceful passing in Washington, D.C. No mention that the “South was right” appears in papers. If the article existed, it would be easily accessible in public archives today, but its absence suggests fabrication. Also, concerning the Scottish Rite Obituary, the Scottish Rite (Southern Jurisdiction), where Pike served as Sovereign Grand Commander from 1859 until his death, published tributes in their official journal, The New Age Magazine (predecessor to The Scottish Rite Journal). A review of digitized issues from 1891 available through Masonic libraries and online show obituaries emphasizing Pike’s philosophical contributions (Morals and Dogma), poetry, and Masonic reforms. There is no reference to Confederate loyalty or the quoted words. The Rite’s records portray Pike as a unifying figure post-war, avoiding sectional rhetoric to promote national reconciliation. There are also no verifiable records of Dr. James A. Henry (although a real Little Rock physician and Pike acquaintance) documenting this statement, which would exist in medical journals, personal papers, or Masonic archives. Searches for Henry’s writings or correspondence provide no sources tying Pike to this quote. Pike died at the U.S. Capitol’s quarters), and there are no witness statements that corroborates the deathbed story.

There is no newspaper article, obituary text, or Dr. Henry’s own account (e.g., no letter, affidavit, or medical note).

Here is another fun one. There is supposedly a letter accompanying his membership dues (dated 15 March 1884), which claims he wrote, “I have never ceased to believe that the South was right, and that the principles for which we fought were the true principles of the Constitution…I shall always be ready to aid in vindicating the truth of history against the falsehoods that have been so industriously propagated.” It is said to be quoted in the Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 12, 1884, p. 287.

The Southern Historical Society Papers (SHSP) was a pro-Confederate publication (1876–1959) known for Lost Cause advocacy. Volume 12 (1884). Well, Page 287 of SHSP Vol. 12 (January–December 1884) does not even contain this letter, quote, or any Pike correspondence. The volume itself is a collection of essays, battle accounts, and society proceedings, in which Pike is mentioned nowhere; and the page is in a section titled “The Battle of Shiloh” (contributed by an anonymous Confederate veteran). It describes troop movements and casualties. This is another fabrication, that is quoted often within neo-Confederate revivalist lore. In this time period, Pike did write letters in 1884 as Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite, often about dues, rituals, or philosophy in relation to ideas of fraternal love and Morals and Dogma revisions. As stated before, his post-war writings avoided Confederate apologetics to focus on national reconciliation and Masonic rules emphasizing unity over division.

It first circulates in unsigned 1920s–1930s pamphlets, e.g., in United Daughters of the Confederacy bulletins without sourcing, then in online forums. Historians, e.g., in The Journal of Southern History agree it is unverified, contrasting Pike’s documented reluctance, where in 1870s letters he laments the war’s follies on both sides, and aided Native American reparations against Confederate treaty breaches.

It is claimed, that Pike wrote in an 1886 letter to former Confederate General Jubal A. Early (president of the Southern Historical Society), that “The more I reflect upon it, the more I am convinced that we were right in 1861, and that the war was forced upon us by fanatics who had neither respect for the Constitution nor love for liberty…The South fought for the same principles that actuated our fathers in 1776.” This is supposedly from the original manuscript in the Jubal A. Early Papers in the Library of Congress.

Jubal A. Early Library of Congress papers (1829–1930) are partially digitized and fully cataloged at loc.gov. There is no 1886 letter from Pike. Early’s correspondence includes Southern Historical Society materials (Jubal A. Early led it from 1870–1894), but Pike’s name appears only sporadically (e.g., in regards to pre-war legal ties), with no post-1865 articles indexed among these papers. Reputable scholars would have reproduced evidence of this.

While Brown’s 1997 book (pp. 451–452) discuss Pike’s post-war D.C. life, Brown draws from unpublished sources, there are no reviews or citations that reference this letter. Brown’s work pushed against Pike myths (e.g., KKK leadership) and focuses on verifiable documents. If the quote existed, it would be footnoted, but even secondary sources citing Brown (e.g., Encyclopedia of Arkansas) omits it. There was an attempt to incorporate Pike into a narrative as a sectional martyr in twentieth-century embellishments, despite well-documented evidence of Pike’s post-1862 disillusionment with the Confederacy.

Let’s return to the claim involving an unverified 1887 letter to Confederate General Daniel H. Maury quoted earlier, in which the full context of the matter is discussed in this statement: “I have never for one moment regretted the course I took in 1861…The old order was the best the world ever saw for the negro and the white man alike. The South was happier, more prosperous, and more truly free before the war than it has ever been since…I shall go to my grave believing we were right.” The original letter is supposedly claimed to be preserved in the Daniel H. Maury Papers at the University of Virginia.

It turns out, that there is no 1887 Pike-Maury correspondence. The embellished quote utilizes Lost Cause rhetoric, which fits Pike’s racism. The Maury Family Papers (e.g., 1786–1995; 1793–1874) are cataloged and partially digitized. They contain extensive correspondence on business, naval affairs, and family matters, e.g., letters from the 1820s–1870s involving Richard Brooke Maury and relatives, but no items from Albert Pike. It would be indexed in inventories, but it’s absent. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas cover Pike’s post-war years without referencing this letter; and Walter L. Brown’s A Life of Albert Pike (1997, p. 448) does not mention it. Allsopp’s work discusses Pike’s Confederate service, poetry, and Masonry around those pages, but searches for “Maury,” “1887,” or the quote isn’t noted. Bibliographies of Pike’s writings (e.g., 1920s compilations) list no such letter. Allsopp, an Arkansas journalist, was sympathetic to Pike but based his biography on available records.

While the Maury Papers collection (MSS 543) does exist at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, the specific letter containing the quote about regretting the course of the Civil War is not a genuine document and is not catalogued within the collection. The alleged letter and quote are fabrications that do not appear in the Maury collection. The detailed description of the collection’s scope and contents available via the UVA Library’s online guide does not list any such correspondence with Albert Pike. The detailed description of the collection is a common feature of online misinformation related to this quote. The precise (but false) archival details are part of the fabrication designed to make the claim appear credible and harder to immediately debunk without contacting the archive directly. This hoax is part of sophisticated misinformation found online that mimics legitimate archival citations relying on the fact that most people will not physically contact the University of Virginia’s Special Collections Library to verify the claim. The quote itself is widely considered a modern invention used to promote specific historical viewpoints.

Here’s one of the first ones I came across years ago. In 1889, in his last major public address, it is claimed that Pike’s speech took place at the dedication of the Albert Pike Memorial Temple, Little Rock. As reported in the Arkansas Gazette, 12 October 1889, Pike said of the Confederate dead, “They died for the holiest cause for which men ever fought…They were not rebels; they were patriots defending their homes and their rights against invasion and tyranny.”

How much of this did you believe? The Albert Pike Memorial Temple in Little Rock (a Scottish Rite Masonic center) was dedicated on May 11, 1922. That’s over 30 years after Pike’s death on April 2, 1891. Archival records confirm the cornerstone-laying ceremony on that date, covered in the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat with front-page articles detailing the Masonic event, with no Pike involvement). No 1889 dedication even occurred. The building’s construction began in the early twentieth-century as a posthumous tribute. Pike could not have spoken there in 1889.

Romanticizing the Confederacy as a “holy” defense against “invasion and tyranny” aligns with Lost Cause rhetoric, but appears nowhere in Pike’s verified orations. His actual last major public address was likely a Masonic event in Washington, D.C., in the late 1880s, emphasizing philosophy over sectionalism. Biographies mentioned document Pike’s final years as reclusive Masonic work in D.C., with no Little Rock trip or Confederate-themed speech that year. Pike avoided overt public Lost Cause advocacy to preserve his federal pardon and Masonic non-sectarian stance. These unsubstantiated myths are common in pro-Confederate literature, in the attempts to conflate Pike’s brief war period onto his Masonic-focused later life. Pike’s true legacy is a case of ideals of universalism conflicting with and developing alongside racism.

In an 1890 final letter to the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction, which was read aloud after his death in 1891, Pike’s last written message to the Council (dated 20 December 1890) is said to contain this passage: “I have never repented of the part I took in the war…I still believe the South was right, and that the principles of State sovereignty and constitutional liberty for which we contended will one day be vindicated.” The Proceedings of the Supreme Council, Southern Jurisdiction, 1891 (pp. 37–38) are quoted as a source.

This final letter is a compete fabrication. The quote’s sectionalism (“South was right,” “State sovereignty”) directly contradicts the Scottish Rite’s post-war emphasis on national unity and reconciliation, which Pike helped enforce as Sovereign Grand Commander (1859–1891). Furthermore, The Proceedings volumes for the Southern Jurisdiction (official records of triennial meetings, available in Masonic libraries and partial digital scans via Internet Archive) exist, but the 1891 edition focuses on Pike’s obituary, tributes to his Masonic reforms (Morals and Dogma), and administrative reports. Pages 37–38 in the 1891 session minutes discuss routine Rite business (e.g., committee reports on rituals), not a Pike letter or war vindication. No references to such a document appear in Rite histories or bibliographies of Pike’s writings.

Also, Pike’s verified last writings, e.g., 1890 Masonic bulletins in The New Age Magazine address philosophical revisions and fraternal harmony, avoiding Civil War topics to safeguard the Rite’s apolitical stance. His actual deathbed (d. April 1891, from illness in D.C.) involved delirium, with no recorded political statements, or any pre-written, read-aloud letter. Biographies (e.g., Walter L. Brown’s) document his final months as introspective and non-sectional, with no such letter cited.

The clever embellished story ignores Pike’s efforts to depoliticize the Rite amid Reconstruction scrutiny. Authentic proceedings emphasize his “tolerance and charity,” and reflect his magnum opus, Morals and Dogma, as the word he left to humanity publicly, despite any private thoughts and limitations.

CONCLUSION

While Pike did engage with comparative mythology on the roots of Indo-Iranian and Indo-European cultural roots and religion, this was not as a supremacist inheritance for Freemasonry. Indo-Aryan Deities and Worship as Contained in the Rig-Veda (1872) and Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine as Contained in the Zend-Avesta explores Vedic and Zoroastrian parallels to Masonic symbolism (e.g., light vs. darkness dualism). In Morals and Dogma, he teaches universalist themes, portraying Freemasonry as a perennial philosophy blending Egyptian, Kabbalistic, and Aryan (Indo-Iranian) wisdom, not a direct inheritance of racial superiority. It in instances reflects his paternalistic attitude common in the colonialist mind. Racism does not negate the purpose underlying his philosophical works. This is just an example of his philosophical views existing alongside the belief in that period of the beginnings of scientific racism, that Black people are not “fully human” — ideas the traditions of the ancestors of Black Americans negated.

We know, that moral blindness and acceptance of racism in any era is no excuse. The same era Pike lived in produced people both White and Black who rejected slavery (as Pike did in his early years) and racial hierarchy such as G. Mazzini, John Brown, Garrison, Sojourner Truth, David Walker and others.

In subjugation however, whether by White, Arab and African slaveholders, many attempts were taken to beat out of Black people the traditions, culture, languages, or roots which give so many other people their strength and firm placing in the World, and certainly against oppression and slavery of all kind. Acknowledging the complexities and hypocrisy is part of the history. One could speak in universalist terms, while at the same time excluding Black people. Such beliefs re-emerge strongly in our day in an attempt to threaten the already fragile boundaries between the regions of the United States beyond Pike’s war days.

The statue of Pike in Washington, D.C.’s Judiciary Square was erected in 1901 by Scottish Rite Freemasons. It is technically the only outdoor monument in the nation’s capital honoring a Confederate general, but it was explicitly designed not as a Confederate tribute. The statue however is a reminder of the pain and wounds from and after Reconstruction era. Pike is shown in civilian Masonic robes, holding a book and facing a Masonic goddess figure symbolizing Scottish Rite ideals. The inscription on the pedestal celebrates him as an “author, poet, scholar, jurist, soldier, orator, philanthropist, and philosopher” with “soldier” buried in the list, with no reference to the Confederacy. The memorial’s dedication ceremony in 1901 emphasized his literary and Masonic contributions, with only fleeting mentions of his Civil War role.

Morals and Dogma was not Pike’s final work, but his magnum opus; and in it, he mirrors Morya’s defense of Buddhism in India in The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett.15 Pike asks his readers to reflect upon the influences of classical Indian Philosophy and the Gymnosophists, who did influence philosophical thought in the Hellenistic world and early Christian asceticism. Although, there is no evidence that the Gymnosophists influenced the Celtic Druids, as Pike seems to suggest, the Druids and Gymnosophists share great similarities in their culture and teachings.

“Those who so associated themselves formed a Society of Prophets under the name of Samaneans. They recognized the existence of a single uncreated God, in whose bosom everything grows, is developed and transformed. The worship of this God reposed upon the obedience of all the beings He created. His feasts were those of the Solstices. The doctrines of Buddha pervaded India, China, and Japan. The Priests of Brahma, professing a dark and bloody creed, brutalized by Superstition, united together against Buddhism, and with the aid of Despotism, exterminated its followers above ground. But their blood fertilized the new doctrine, which produced a new Society under the name of Gymnosophists; and a large number, fleeing to Ireland, planted their doctrines there, and there erected the round towers, some of which still stand, solid and unshaken as at first, visible monuments of the remotest ages. What we have done for ourselves alone dies with us; what we have done for others and the world remains and is immortal.”

Albert Pike, Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. Charleston, SC: Supreme Council of the Thirty-Third Degree for the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States, 1871, pp. 278–279

Primarily, this is an attempt to understand prolific individuals and key currents of esotericism in American literature and philosophy. Yet, it is hoped that a better legacy from contemporary esotericists and students can be left to the next generations, that do not repeat the limitations of past notable figures and works.

FOOTNOTES

- Walter L. Brown, A Life of Albert Pike, 1997, p. 98. ↩︎

- Brown, A Life of Albert Pike, pp. 248–255; original issues Arkansas State Archives. ↩︎

- See Post-war support for Prince Hall recognition in Pike to Prince Hall leaders, 1875 correspondence, reprinted in Wes Cook, Prince Hall Freemasonry, 1976. ↩︎

- “Why did the KKK have weird Titles” on Reddit challenges Pike’s influence on the KKK. ↩︎

- According to Walter Lee Brown in A Life of Albert Pike (1997, pp. 44–47) and Frederick W. Allsopp in Albert Pike: A Biography (1928 work is a more substantial biography published by Parke-Harper), pp. 67–69. An earlier biography by Allsopp is titled The Life Story of Albert Pike also published in 1920 by Parks-Harper. ↩︎

- Refer to Godwin, The Theosophical Enlightenment, 1994; pp. 192–194; Deveney, Paschal Beverly Randolph, 1997, pp. 312–314. ↩︎

- Brown, A Life of Albert Pike, p. 412 ↩︎

- This can be seen in Pike’s work, Indo-Aryan Deities and Worship as Contained in the Rig-Veda, 1872 preface; see Brown, Life of Albert Pike, pp. 389–391 ↩︎

- This was documented in de Hoyos, Albert Pike’s Morals and Dogma (Annotated Edition, 2011, pp. xv–xix) and Scottish Rite Ritual Monitor and Guide (3rd ed., 2010, pp. 87–92), and in Tresner’s Albert Pike: The Man Beyond the Monument (1995, pp. 112–118). ↩︎

- Continued support for Southern ideologies in collections of Albert Pike’s letters from the post-Civil War period on Arkansas Studies, including those to his son Luther H. Pike, and particularly John C. Peay written between 1861 and 1889. ↩︎

- Brown, A Life of Albert Pike, pp. 305–307. ↩︎

- Shea & Hess, Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West, 1992, pp. 289–294; Bearss & Gibson, Fort Smith: Little Gibraltar on the Arkansas, 1969, pp. 212–215. ↩︎

- Brown, A Life of Albert Pike, pp. 378–385. ↩︎

- See Introvigne, Satanism: A Social History, 2016, pp. 188–198. ↩︎

- The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett, no. 134, Dehra Dun, Dec. 4. ↩︎

Leave a comment