Bertrand’s narrative attributes Europe’s secular turn largely to a linear transmission from Zhou dynasty ideas through Jesuits to Voltaire, framing it as the “single decision that most shaped China’s destiny” and by extension, the world’s. However, republicanism’s origins lie in a grand eclectic tradition, including Pre-Socratic sages, Stoicism, Cicero’s republic, and Petrarch’s revival of letters, extending through Charlemagne’s commonwealth to the American and Haitian revolutions. My work attempts to reveal a more nuanced, eclectic foundation for American Republicanism that challenges Bertrand’s emphasis on Chinese secularism as the primary driver. My exploration into republican roots as a continuous civic republican tradition combating arbitrary power traces influences back to classical antiquity, ancient theosophies, and a blend of theistic and philosophical sources, suggesting that Enlightenment secularization was neither solely Chinese-derived nor purely atheistic, but intertwined with spiritual and Western classical elements. I argue, that the West is in the state it is in, not merely because of economic materialist causes and systems, but because it is ignorant of this full history, and in this ignorance has limited its expressions, true creative potential and ability to uniquely combat its problems. It doesn’t need China’s system.

A Critique of Arnaud Bertrand’s Post on China’s Secular Civilization

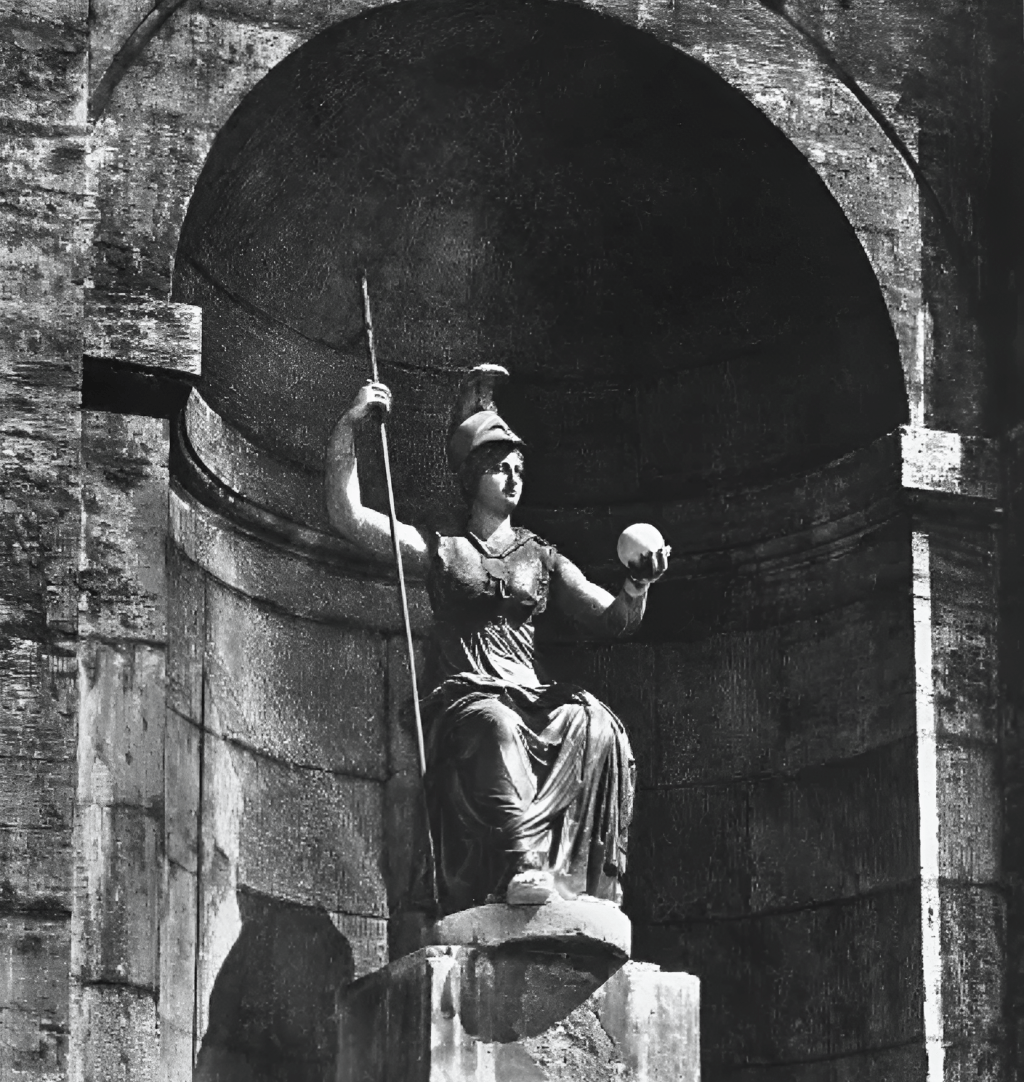

Arnaud Bertrand is an entrepreneur and commentator on economics, geopolitics and writes about China in which he lived. The viewpoint is the kind that my writings counter. I also have had a long interest in China, its history, philosophy, cultures and development; and my interactions with fellow Chinese international students is partly what led to the very existence and title of my blog, The American Minervan. There was an issue I had with his latest post leading to his article, The civilization that never needed God. Titles on YouTube that feature him are “The West cannot beat China,” “Globalist Death of France and Germany” as a criticism of NATO and the European Union.

I quoted his post https://x.com/RnaudBertrand/status/2020748828497109185 on X which links to his Substack article:

“This is probably the single feature that makes China most unique as a civilization in human history: it is pretty much the only one where religion never had a say in political affairs. We often wrongly believe that China’s secularism came with Communism but this couldn’t be more wrong. The roots are far, far more ancient than this. Think about any other civilization – India, Persia, ancient Egypt, European civilization, the Incas: they all had a priestly class that held considerable political power. China? Never. Never, ever? Actually China, in its very early history, had a brush with theocracy during the Shang dynasty in the 2nd millennium BC. And it is precisely this episode – or rather what came afterwards – that decisively de-linked religion from government affairs. How so? Because around 1046 BC, the Zhou overthrew the Shang and immediately faced a big problem of legitimacy. The Shang had claimed to rule because Heaven had chosen them. If that were true, then the Zhou had just committed the ultimate act of sacrilege. How do you justify going against God’s will? The answer the Duke of Zhou (who can thus be credited as the – perhaps unwitting – inventor of secularism) came up with was essentially to say that Heaven’s mandate is not a birthright but a contract – conditional on the virtue of the ruler and good governance. It might not sound like much but this idea completely changed the whole equation: suddenly the legitimacy of power didn’t rest on God’s will but on man’s moral judgement, on whether the ruler had virtue (德, Dé) and governed well. Which meant that, ultimately, the people – as opposed to a God – became the arbiter of whether a ruler is legitimate. If there is one single decision that most shaped China’s destiny as a civilization, it’s probably this one. And, as I explain in my latest article, it ultimately shaped all of us in profound ways: through a chain of events involving Jesuit missionaries, Voltaire, and what French Enlightenment thinkers called “l’argument chinois” (“the Chinese argument”), it is this very idea that ended up secularizing Europe too and drove the Enlightenment movement. That’s the topic of my latest article: the origins of China’s secularism, how it shaped three thousand years of Chinese civilization, and why – far from being a belief in nothing or an absence of belief as it’s all too often depicted – it’s on the contrary a faith in humanity itself.”

Arnaud Bertrand

I have advocated for a revival of classical republicanism rooted in an unyielding faith in humanity’s inherent dignity, and so I find Bertrand’s exploration of China’s secularism both intriguing, but ultimately incomplete. Bertrand’s post highlights China’s unique historical detachment from theocratic governance, tracing it back to the Zhou dynasty’s revolutionary reinterpretation of the Mandate of Heaven (天命, Tiānmìng) as a conditional contract based on virtue (德, Dé) and good governance, rather than divine whim.

This shift, as Bertrand aptly notes, positioned the people as opposed to a God as the arbiter of whether a ruler is legitimate. It’s a compelling narrative that actually corresponds to certain republican principles: the emphasis on moral judgment, civic virtue, and the people’s role in legitimizing (or overthrowing) authority; all which is emphasized in the classical republican insistence that freedom is non-domination, sustained through vigilant citizenship.

In my open letter, Every Citizen is the Salvation of the Republic, I argue that the republic’s salvation lies not in distant gods or elites but in every individual’s capacity to embody virtue and hold power accountable, much like Bertrand’s description of the Duke of Zhou’s innovation democratizing legitimacy. However, Bertrand’s framing of Chinese secularism as “a faith in humanity itself” and his bold title, “The civilization that never needed God,” reveals a critical flaw when viewed through the lens of republicanism. I emphasize that faith in humanity is not a secular void or mere “belief in nothing,” as Bertrand critiques common misperceptions, but rather a recognition of human dignity from the very nature of motion and life itself that was taught, passed and secularized from the Pre-Socratic and African philosophies to the Stoic and Christian belief that resides in every person. This spark, universal in its Enlightenment pre-racialized form is what was taught as endowing humans with inalienable dignity and the revolutionary power to resist domination. Bertrand’s account, while praising humanity’s moral agency, strips away this foundation, reducing it to a pragmatic, atheistic humanism born from political necessity.

He writes that the Zhou’s solution “completely changed the whole equation: suddenly the legitimacy of power didn’t rest on God’s will but on man’s moral judgement.” But in republican thought, moral judgment isn’t self-generated in a godless vacuum; but is ignited by our inner divine essence, which proves our equality and demands the overthrow of oppressive systems. Without it, as I warn in my article, atheistic theories ignore the full depth of human nature, leaving societies vulnerable to new forms of domination, be it imperial bureaucracy or modern authoritarianism.

Consider the historical parallels Bertrand draws: the Shang dynasty’s theocracy, with its brutal human sacrifices, gave way to Zhou secularism. This mirrors how classical republicans, from Cicero to the U.S. Founders rejected tyrannical divine-right monarchies in favor of virtue-based governance. Yet the Founders’ hypocrisy professing equality while practicing enslavement gets into the gap Bertrand overlooks in China. He claims China’s secularism shaped a civilization where “religion never had a say in political affairs,” influencing Europe’s Enlightenment through Jesuits and Voltaire’s “l’argument chinois.” But republicanism, as I argue, was most fully lived not by elites but by the oppressed: enslaved people like Epictetus or Harriet Tubman, who embodied Stoic endurance and Epicurean pursuit of happiness under the pressures of injustice. Their faith wasn’t in abstract humanity but in the divine spark that fueled resistance.

Bertrand’s China, for all its emphasis on the people (as seen in phrases like “人民万岁” or Mencius’ prioritization of the people over the sovereign), historically evolved into centralized empires where citizen agency was often theoretical, not practiced through republican institutions like mixed government or civic assemblies. This secular “faith in humanity” risks becoming a tool for state legitimation rather than genuine non-domination, especially in modern contexts where governance prioritizes harmony over contestation.

Bertrand’s narrative attributes Europe’s secular turn largely to a linear transmission from Zhou dynasty ideas through Jesuits to Voltaire, framing it as the “single decision that most shaped China’s destiny” and by extension, the world’s. However, republicanism’s origins lie in a grand eclectic tradition, including Pre-Socratic sages, Stoicism, Cicero’s republic, and Petrarch’s revival of letters, extending through Charlemagne’s commonwealth to the American and Haitian revolutions.

Enlightenment figures like Voltaire used China rhetorically to attack European clericalism, but this was often idealized and selective, ignoring China’s own ritualistic and imperial elements that Jesuits adapted to fit Christian narratives1.

The sinophilia is nauseating and promotes a distorted oriental despotism to undermine Renaissance ecumenism, as seen in Leibniz’s efforts to compare Confucianism with Christianity, rather than using it to erode faith.

By centering “l’argument chinois,” his position ignores internal European developments, such as the Crusades to Renaissance timeline (1075-1680) blending occultism with Enlightenment rationalism. American Republicanism inherits this hybrid. These elements retain a moral framework tied to theism, unlike Bertrand’s claim of thorough secularization. Many Enlightenment thinkers were deists, not atheists, viewing reason as compatible with a divine order (see Engagement with China and the Enlightenment), and American founders like Jefferson drew more from Locke and Montesquieu with classical Greco-Roman influences, rather than Chinese models.

Moreover, Bertrand’s conclusion that Chinese secularism is “on the contrary a faith in humanity itself” ignores how republicanism integrates the spiritual to combat modern ills like structural racism and capital domination. In my view, racial hierarchies and white supremacy are absurd precisely because they reinterpreted the notion of the universal divine spark or fragment of God; a denial perpetuated by Enlightenment “objectivity” that racialized human rights. China’s model, as Bertrand presents it, offers a counter to Western theocracies. Without acknowledging these roots, it falls short of the radical republican philosophy: every citizen as the republic’s salvation, discerning corruption and embodying virtue to restore non-domination. Bertrand’s worker “conquering Heaven” is poetic, but in republican terms, that conquest is divine work with humans as co-creators, not replacements for new gods of technology. In sum, while I applaud Bertrand’s illumination of China’s humanistic legacy and its global ripple effects, his godless secularism misses fire that republicanism demands for true human flourishing. To salvage any republic, we must trust not just in humanity’s judgment, but in the sacred human dignity that makes such judgment possible.

Over-secularization risks eroding the theosophic core sustaining republican virtue. Bertrand’s narrative, while intriguing, risks ahistorical Sinocentrism by portraying Europe as passively “secularized” by China2, ignoring how Jesuit reports were tools for European debates. In the American context, republicanism’s roots in Puritan covenantalism and classical liberty integrate the sacred, fostering resilience against arbitrary rule without needing full secular detachment.

While Chinese ideas contributed to Enlightenment discourse, the thesis overstates their role in driving secularization due to its actually eclectic, theistically infused origins. The facts reveal republicanism as a timeless struggle against tyranny, integrating from and articulating diverse ancient wellsprings beyond Chinese primacy. China pulls from its lessons learned as an ancient civilization, and China continuously evokes the argument that its success means that its system works, while ours does not. We are capable of doing the same, and we are capable of doing that without the dominance of artificial intelligence, and the modern Chinese model through its integration of Marxism.

FOOTNOTES

- See Michael O.Billington, The European ‘Enlightenment’ & The Middle Kingdom ↩︎

- A source on China’s influence on the Enlightenment for those interested, The First Global Turn: Chinese Contributions to Enlightenment World History, pdf. ↩︎

Leave a comment